The Dynamic Process of 'Transitions'

This Week’s Topic

This week I’m pleased to welcome new DIR Expert Training Leader, Helen Groth, as my guest to discuss the dynamic process of ‘transitions’ in autism. Helen gave a fabulous presentation on Transitions at the International Council on Development and Learning (ICDL) 2022 Virtual DIR/Floortime Conference that I took so much away from and I am so excited to welcome her this week to share her presentation material with us!

This Week’s Guest

DIR Expert Training Leader, Helen Groth, is a British trained, dynamic special educator currently living in Milwaukee, Wisconsin who has a private practice called Play Potential. Although she hails from the United Kingdom, Helen spent many years living and working in Singapore. Her work is rooted in relationships: building trust with families through respectful interactions. She is a life-long student who is always reading and learning through additional training and mentorship.

What is a ‘Transition’?

When Colette Ryan presents, Helen starts, she always starts with a definition. The dictionary says that a transition is “the process or period of changing from one state or condition to another” or “the act of experiencing a change“. Helen finds that looking at synonyms can also be helpful: flux, growth, switch, shift, adjustment, adaptation, transformation, or evolution. For Helen, a transition involves two things: the capacity to stop what you’re doing currently, and the capacity to start doing the next thing.

This process can seem simple, but it can stir up such strong emotions in our kids, such as at school drop-off. Autistic self-advocate, Kieran Rose discussed in a past podcast how neurodivergent individuals get immersed in what they’re doing and it’s like having to suck them out of a black hole and having to focus on something else. At my son’s nursery school the teachers used a catchy song whenever the kids had to transition–a tool to aid with the transition.

Helen asks what it is that causes that dysregulation in a child after being so calm in their activity? Think about the example of enjoying a playground (having fun moving and swinging and sliding) and then what happens when you have to leave and get into your car seat (which restricts your movement so much). What about new shoes or new clothes? It can even simply be that you washed the leggings and now they’re more snug, Helen continues.

One phrase Helen used during the presentation that stuck with me was the description of a transition being “moving from the known to the new“. Many of our children cannot picture what is not right in front of them and they are living in the moment, so they are doing something familiar and organizing then suddenly have to move on to something they have no concept about, which is very dysregulating for them.

Transitions as Stress

Helen recalls that at the ICDL Conference last October, Stuart Shanker defined ‘stress’ as anything that causes us to burn energy to maintain the body’s homeostatis. We turn this stress off for children through our Relationship, Helen explains. We don’t want anyone to be doing this transition independently, Helen says. We want them to be doing it interdependently within that relationship with their caregiver, with their teacher, etc. so they have that support in place to move from the known to the new.

While novelty and ‘the unknown’ can often cause great stress to our kids, some kids can feed off of novelty as well. My son loves going out to restaurants and going to hotels, which are different every time experiences and if around his area of interest, he loves going to new places. It’s part of the frustration for parents that our kids are fine doing some things, but not others. We often wonder what’s going to set off my kid today? And being tired, sick, or hungry, among other things, can affect how they react to transitions as well.

That’s the ‘I‘, Helen points out. It’s the individual characteristics of our children in each moment. It’s about us being able to read their cues, she explains, and about supporting our child to be a strong cue sender as well. Novelty creates alertness in their system, captivating them. Without that novelty, Helen says, some children can quickly get bored. But with our Floortime eyes we can see the safety in predictability. Some people can see that as rigidity, but it can be regulating and organizing, Helen offers. We need to be in the moment and be present to what’s happening, keeping our calm and cool.

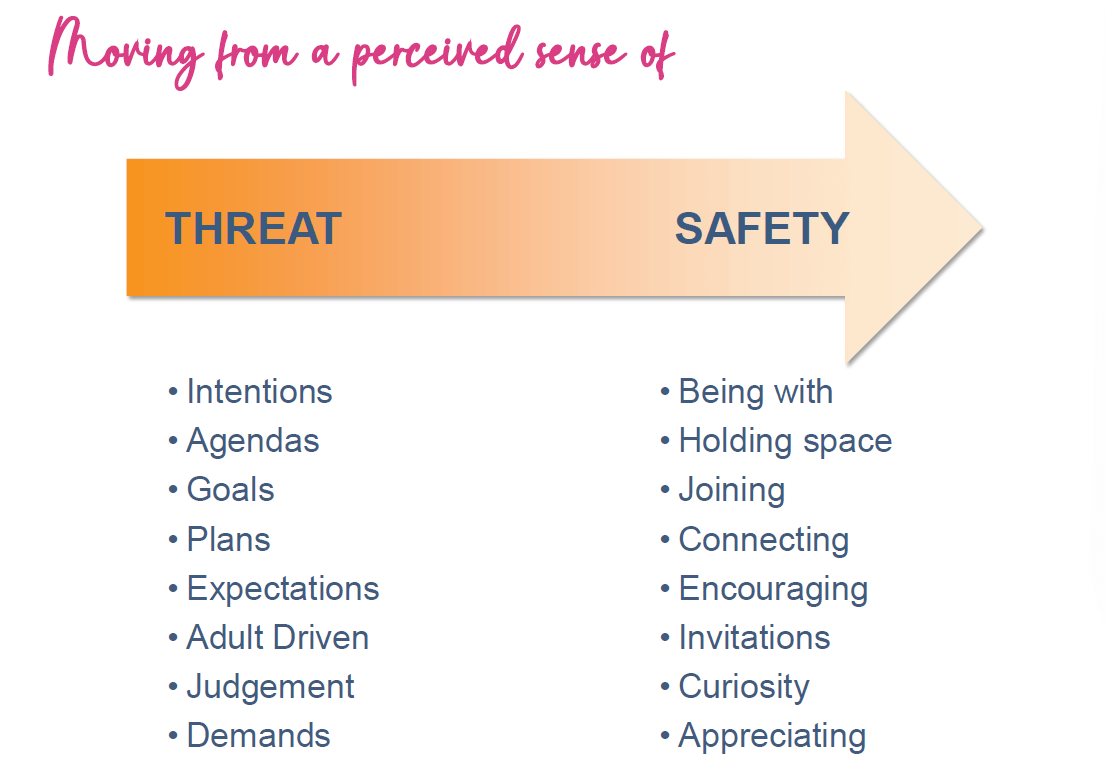

I asked Helen what’s happening in the brain during transitions. It depends on which state you’re in, Helen answers. How can we use ourselves to turn the child’s flight or fight response off by being with the child in a very gentle and soft way, having an invitation to engage, reducing that threat level to get back to that safety zone for them. We’re not adding another demand on them, Helen outlines.

Referring to the slide from Helen’s 2022 conference presentation seen here, if the child is feeling any of the things in the left column, it is threatening to them. The child gets a sense of safety from things on the right side of the slide which support this ‘felt’ sense of safety, rather than a ‘don’t touch it because it’s hot‘ safety, Helen clarifies. It’s an internal radar, or a neuroception that Stephen Porges talks about which is a subconscious sense that we are safe and that the Relationship we are in is nurturing and pleasurable to us. We can thrive and move from one thing to the next thing when we’re in this sense of safety.

How can we support and scaffold transitions?

If a practitioner has a 45-minute appointment with a child and the child screams for 20 minutes, the therapist feels they can’t do what they want to do in the session, and the parent is frustrated they paid for a full session but lost half of it. Helen says we need to drop that agenda of our own to give the child what they need in the moment by supporting them. Instead, we need to modify ourselves and our Relationship, building the capacity to shift from one thing to the next. There’s a learning opportunity for everybody to be in the moment together, to learn together, and co-regulate together. Get rid of the need to move on, Helen stresses.

Helen says it’s about just ‘being’ with somebody, honoring that person, and connecting with them. We need the whole range of emotions. Some emotions are easier for a parent and some are less easy, Helen offers, but children need the experience of having a challenging moment and knowing they’re cared for and valued through all of these emotions, Helen assures. This is something a lot of people overlook, I add. ‘The work‘ is the meltdown. It’s the most stress I’ve experienced when my son is stressed. What better way to lower our stress than to learn how to deal with what to do when we are stressed?

What can we do for both of us to get regulated again? Helen says it’s about the capacity to stay in the moment, whatever the moment is, whether we’re experiencing pleasure eating ice cream or when we hear the ‘shark music’ from Circle of Security. We’re giving our children opportunities to practice with us when they are disorganized and dysregulated, Helen says, because it’s scary feeling disorganized and dysregulated with unfamiliar adults. We are giving them repeated experiences, safely. There’s no rush in Floortime. “You’re creating an intentional pause that feels like an invitation.” Slow down and stay in the moment, she suggests.

And sometimes our kids will mask in front of strangers because it doesn’t feel safe to meltdown, so the parents experience all the meltdowns, I add. We’re creating a space for them to initiate into, Helen repeats. It’s not us leading with our agenda, but us creating that pause–that safe landing space–and waiting for them to initiate, as suggested in my ‘Going slower to move faster‘ podcast. When we provide that gift of time, Helen continues, it gives us the opportunity to adjust, shift, and reconnect. Then the child can adjust and shift in their body and find meaning in it. We always feel like we have to solve it, I add. They have to learn to solve it for themselves with our help. We want to be that safety buffer while they figure it out.

Wondering questions

These are ways of adjusting ourselves and ways of being with our child, Helen suggests. We can also ask ourselves wondering questions to support ourselves in the moment, to have a curious mindset, and to be non-judgmental to guide your thinking in the moment. You might do this when watching a video of a recorded session, she continues. Frame the self-reflection with wondering questions. If we think about the Floortime model, to frame all of our thinking, we want to look for their strengths and wonder how we can build from those to support vulnerability:

- What’s disrupting the interaction?

- What are the child’s vulnerabilities and what we can do to scaffold and support them?

- How can we adjust and attune ourselves so we can support the child and ourselves in this moment?

- What will it take for this individual to feel safe in a new situation?

- How do we create safety for them? What will they need?

- What does this individual find comfort in?

- How big is that transition for the child? Is it a big moment or a smaller transition moment?

- What is their experience with transitions? Have they had moments where they’ve experienced support, scaffolding, empathy and respect? Or have they had stressful moments of being hurried with an adult’s agenda because sometimes we have to get to the dentist or to school?

- Is there a motivator I can harness or a de-motivator I can evaporate?

- If these difficulties are happening in a session, how is the parent feeling in the moment and how can we support them as well?

- What’s the meaning for the child in the transition?

Be Playful

Helen says that we can create fun in the movement from A to B such as a transition song, or by using scooter boards to experience fun during the transition, as Gretchen Kamke says. We’re not looking for an answer, Helen states, but we are supporting our own regulation. We add the cognitive piece where we can try to scaffold our thinking and ways of being through considering different aspects of the transition moment, she says. Floortime is all about the playing. There’s so much complexity supporting play in our ways of being with that other person.

Our playfulness supports the foundation of safety, Helen states. It supports the brain to function as an integrated whole so we don’t lose the brain-body connection that Mona Delahooke talks about. Through our playing and depth in it, it’s through our therapeutic use of self and in the intentional decisions we’re making in the moment to support the child, informed by self-reflection and wondering questions, Helen says. We come along side the child, following the child’s lead, be together, join the child’s world rather than pulling them into ours to follow our agenda, pause and wait–actively waiting posing the wondering questions to ourselves internally, being fully available and in the moment, matching their affect and energy and shift.

From there, we’re building rhythmicity, supporting and scaffolding so they can reach that homeostatic state again, building bridges for the child to use, adding structure they can use to support themselves to get to the next spot, and always joining the child first so we can create that shared world and connection. We’re not imposing or directing them, and not controlling or diverting them. The range of emotions is what we need to feel, Helen continues. Consider what’s the right challenge in this moment or the right invitation to create that ‘just right’ success for the child to move through this to get to the next thing that’s creating their uncertainty, Helen says.

Interoception

Staying in the moment and joining the child is so often overlooked. It’s really about empathetically looking at the child and wondering what the child is experiencing right now. It seems abstract. It’s overlooked all the time. Everybody’s trying to rush to the next thing. Sitting in the moment and literally doing nothing but experiencing the child without trying to fix it is difficult for caregivers to do, I state. It’s not something to fix, Helen responded. This moment might be more difficult than the last or the next, but it’s nothing to move away from. It’s just an aspect of life. To experience the joy of life, we have to experience those difficult moments. We have to embrace all of them, Helen insists.

This is the distinction of feeling the transition versus a cognitive memorization of coping through it, I added. Feeling the disappointment of not wanting to leave and being scared that something is about to happen that I don’t want, and being mad that my caregiver isn’t stopping it and being mad at the person who’s making me do this is a process. It gets into the interoception piece. We’re constantly building up a library of experiences that feel safe or not, and we want children to notice what is a good experience and what feels less comfortable for them.

This is important information that keeps our children safe, Helen adds. We want them to know this about themselves and have that internal sense and interoceptive awareness of what feels good to their body and their mind and what feels less good to them because it makes you vulnerable if you don’t know these things about yourself. We want them to have resilience and to have tools for every moment, and to be able to set boundaries for themselves. In a past podcast we talked about the importance of having the opportunity to say ‘no’.

We use our own therapeutic use of self in alliance with the activities the child chooses to set the stage to create that entry point.

Trauma

Sometimes our children’s reactions to transitions could be a result of trauma. We may have no idea what a child has experienced in the past. Transitions cause uncertainty, which is disorganizing for the body and the brain, so we lose that brain-body connection and don’t feel safe. In that sense, transitions can be traumatic for a child. The core of a traumatic moment is that sense of ‘I don’t feel safe‘, Helen explains. It doesn’t have to be a big event or a repeated small event over time, Helen argues. They can be your own body that is a traumatic experience on a daily basis for people. Trauma can be anything that overwhelms your nervous system and we can see there’s big overwhelm in the emotions we see our children experiencing.

The D.I.R. Model

R: We talked about how the Relationship supports transitions. Occupational Therapist, Dr. Virginia Spielmann talks about this saying, “The art of over time modifying the relationship to build each individual’s empowered sense of autonomy.” It’s the individual’s sense of what creates meaning or purpose for them, Helen says. What do we need to do to support somebody to have agency in their transition? It’s not a compliance of ‘just do it’, Helen explains. We want to support them to move at their own pace for their own purpose so their body is organized for that purpose. I add that once you have those ‘pennies in the bank‘ with somebody, a sense of safety comes with that.

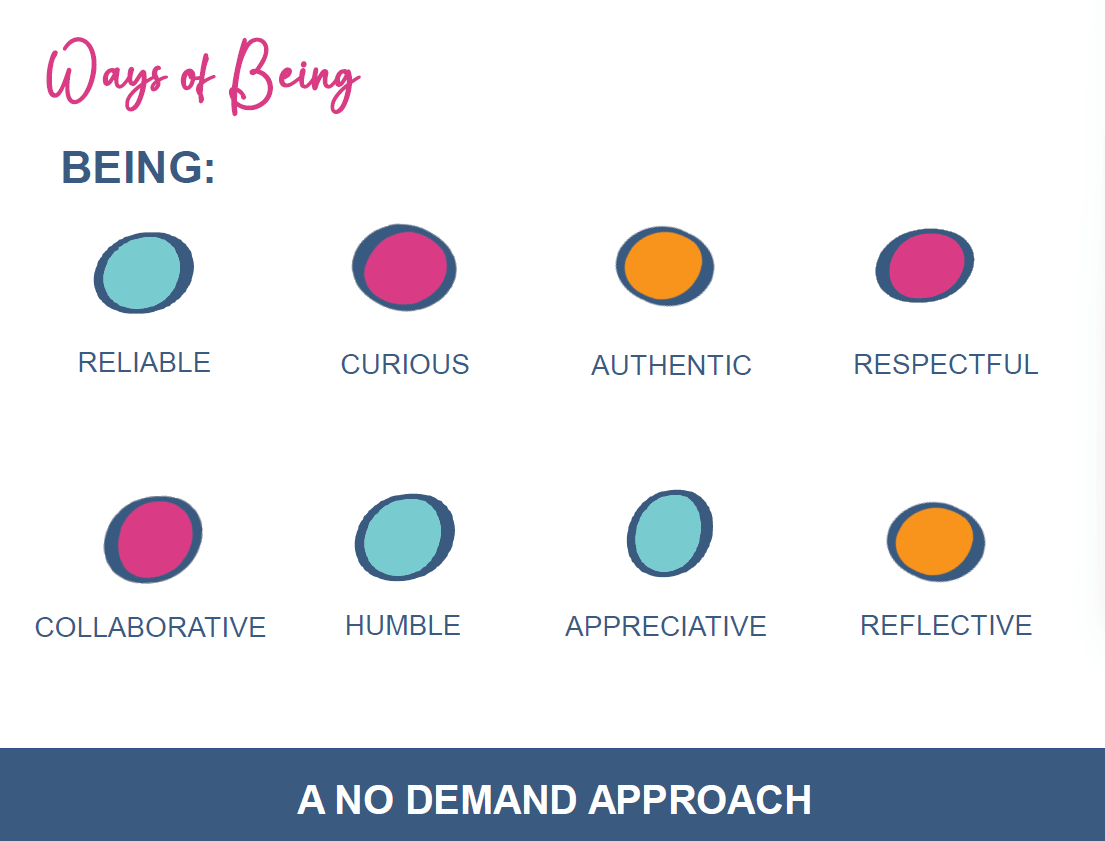

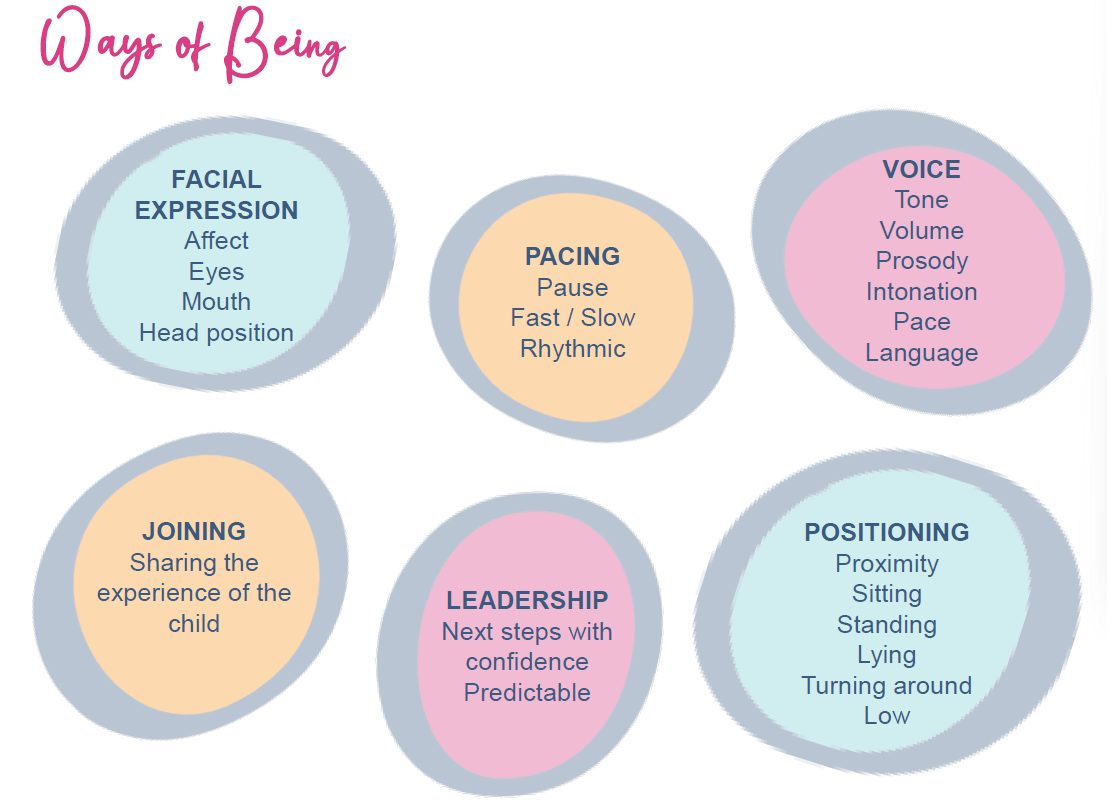

I: Individual differences. Helen talked about children’s sensory systems causing them to feel trauma that many of us don’t notice whether it’s flickering lights, or hearing every noise without filtering out irrelevant sound input, or tactile sensitivities. But our own individual differences come into play as well. Helen showed a couple of slides in her conference presentation about ‘ways of being’ shown here. How we can be all of these things for the child depends on our own ‘I‘ in how we can get into a state where we can be any of these ways. I’ve talked about in the past how if I was outside on the grass in the summer with bees, my capacity for being this way would be much lower.

How we’re positioning ourselves, our facial expressions, etc. all contribute to our emotional tone to the child feeling us, Helen explains. We’re supporting and scaffolding them in the moment. What configuration of these ways of being do we need in any one moment to support the child and ourselves through those transitional moments? The most effective tool in Floortime is ourselves, Helen says. We create that intentional pause for ourselves to be in the moment. These are all tools to create that transition more smoothly. They are ways to hold the space and offering an invitation to the child, Helen says.

D: Developmental capacities. We will cover this in the case study section below.

An ‘Invitation’ Approach

In her conference presentation, Helen had talked about the concept of ‘curiosity’ and “an invitation approach”, defining curiosity as a “lack of hope and expectation” (Frank Ostaseski quote). It’s a ‘just-wait-and-see’ approach, as an observer. It’s ‘wait-watch-wonder’, as we say in Floortime. Curiosity is just essential for Helen, she says, and harnessing that power of curiosity. It’s not judgmental, there’s no agenda to it. It’s information seeking to support. It has a sense of compassion to it and is respectful because you’re not diving in and doing anything, she explains.

We talked about the wisdom quote above that Helen had presented at the conference. Every parent wants the tools and instructions, but it’s important that while you have ideas of what you can try, it’s so important to not put that in between you and the child, otherwise you’re not really in the moment. For Helen that humanity is the respect and curiosity. It’s being with somebody without trying to fix or change anything. It’s much easier said than done, but it’s a take-away for this podcast.

Case Study

A little girl gets very upset, throws toys and pushes other children when the teacher says it’s time to clean up and come to circle time. When the teacher comes to her, she starts screaming and says she’s not ready yet. Many would see the behaviour and say it has to stop. Helen says we need to stop and breathe, and have compassion for this child. It’s a difficult moment, so how can we scaffold and support the child? We need to acknowledge to ourselves this is difficult. Let’s think about how happy she was playing and how absorbed she was in that activity. Pulling her out is causing her intense stress.

Helen says we all do our best in the moment, but in reflection, after the fact, we can do better in the next moment, then the next day we can give more cues and warnings, geared to her. Maybe it’s gently coming over to her personally, maybe it’s giving her a tidy-up job, or maybe it’s 1:1 support from another adult in the room. How can we use this information from this chaotic moment to help us be wiser in another moment in the future? We can’t join this chaos and dysregulation. In the podcast on Self-reg and Floortime, and in Season 1, Episode 3 of ‘We chose play‘, Dr. Stuart Shanker said once you’re in that moment, there’s not much you can do. You can look at what happened just before that moment, then plan better for next time.

The ‘D‘ in DIR/Floortime dictates how far you can challenge someone helping them through the moment. You can come along side and mention what’s coming up and just saying, “Hmm… you don’t want to. We have a problem” and wait. I can do so much more with my son than I could 10 years ago when he was 3. He is able to have back-and-forth interactions while he’s upset now and socially problem-solve. It’s about getting through that moment and thinking ahead until the next time, keeping the child’s ‘I‘ in mind and using that ‘R‘.

There’s such complexity, Helen says. There’s so many aspects of their attention into the activity that they’re doing. Kieran Rose talks about the monotropism of the full focus where there is so much energy and depth of thinking going into that activity and then having to switch. Even with what we’ve covered today, we’ve barely touched on so many aspects of transitions, but I hope the audience has some take aways about staying in the moment, respecting the other’s experience, using the Relationship as a vehicle to transition, and allowing the child time and space to initiate some kind of adaptive response that we can scaffold through the transition.

The Tips and Tools

Helen wraps up with the tips and tools discussed today:

- Don’t be directive or push children through a difficult transition

- Reframe what you think needs to be done

- Think about the child’s experience

- Notice the cues in advance for next time

We get so used to doing things a certain way and our children get used to that and may become reliant on that, so in times of stress when we can’t do those comforting things, then we second guess ourselves. It’s such a dynamic process because not only is every transition different, but we change as our child is also growing and developing as well. It’s about having the capacity to be able to regulate ourselves in whatever moments we find ourselves in as a model for them to be able to regulate themselves in whatever moments they find themselves in.

And what’s too much comfort? Helen says that as much comfort, support and scaffolding as we can give to each other is to be respectful and authentic, and it supports somebody to find their own authenticity, agency, and way of doing something. If you don’t have that sense of comfort, where do you move from? Helen says that having those experiences of safety allows for that spring board. I gave the example of how by the second or third week of school, our children are more used to separating at drop off. So, go at the child’s pace and join them, Helen says. Appreciate where they are, developmentally, and what their journey is.

DIR is a lifespan model, Helen reminds us. There’s no rush in Floortime. There’s no right way or one way, she says. These are just ideas and suggestions to probe our thinking to reflect and invite a different response for next time.

This week’s PRACTICE TIP:

This week let’s practice that intentional pause in moments of dysregulation with compassion and empathy in the safety of your relationship that presents the invitation to engage for the child.

For example: In a moment of dysregulation, stop, come to the child’s level and let them know with your body language and facial expression that you are there with them through this discomfort but stay quiet and calm. Imagine in your head what the child is experiencing, think about what just happened to make them distressed, and don’t try to solve the problem. Just wait, watch and wonder. See if you notice the child move through their dysregulation without you having to do anything for them.

Thank you to Helen Groth for discussing the dynamic process of transitions in autism with us, through a DIR/Floortime lens. I hope that you learned something valuable and will share it on Facebook or Twitter and feel free to share relevant experiences, questions, or comments in the Comments section below.

Until next time, here’s to choosing play and experiencing joy everyday!