Colette Ryan returns this week to discuss cues recognition. She is a Expert Training Leader in the Developmental, Individual-differences, Relationship-based (DIR) Model with the International Council on Development and Learning (ICDL), the Parent Support Specialist at the DIR Institute, a New York State endorsed infant mental health therapist, and an infant mental health fellow at Montclair State University in New Jersey working with Dr. Gerry Costa.

Recognizing and documenting our children's communication cues

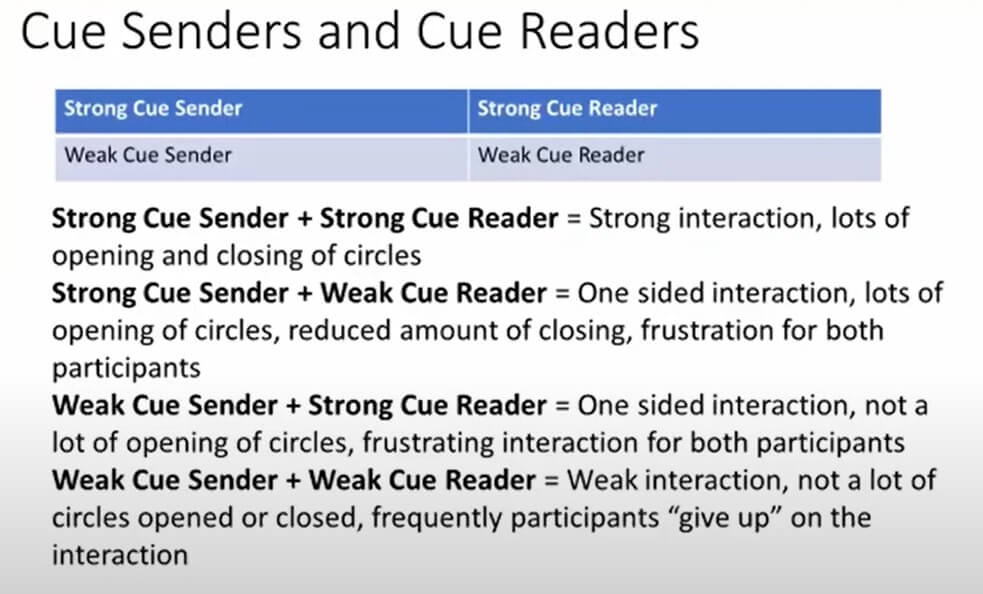

Cue sending and reading

In our last podcast with Colette on meaning making, we touched on cue reading and cue sending. How our child reads and sends cues can really inform us how we’re going to interact with our child and aim for that reciprocity, Colette starts. But sometimes our children’s cues are difficult to read. As parents we usually know our child’s cues but others don’t. Today we want to discuss how we can record these cues in a document to share with others in our child’s life so they can understand what our child is communicating to those around them.

Parents know their kids best.

Cue reading can really impact engagement and reciprocity. Sometimes if our child is not a good cue reader, we get closer, louder and faster, which can overwhelm our child. What our child might really need is for our cue to be quieter and slower. This gives us the chance to repair the rupture by attuning to our child.

Colette says that Dr. Ed Tronick and Dr. Claudia Gold’s new book tells us that learning happens in the moments of discord. It’s the rupture and repair that make the relationship stronger. If we give up after the rupture, we lose out on that chance for rich interaction and getting to know how our child communicates.

Individual differences

Colette adds that the ability to repair varies from day to day. We can be tired, upset or distracted. Having a self-awareness about that is important. Then, thinking about our kids, there are many factors that can affect their ability to send or read cues: being hungry, thirsty, tired and their individual differences. Looking at our child’s sensory processing profiles, we might find that the lights are too bright, it’s too loud, there’s too much visual distraction, they need room to move, or they can’t feel their body in space. This impacts their cognitive load–how much cognitive energy our children have left for cue sending and reading.

Documenting cues

Colette suggests writing down the cues that our children send to us because when these cues are successful, the interaction is successful and they want to do it again. For instance, when my son gets very irritable, it’s usually a sign that he’s hungry. I can let the school know that if he gets very irritable to give him a snack! Colette says other caregivers are appreciative to receive these tips from parents! She gave an example of a child who curled his toes when engagement got to be too much! That was a sign to step back and re-attune.

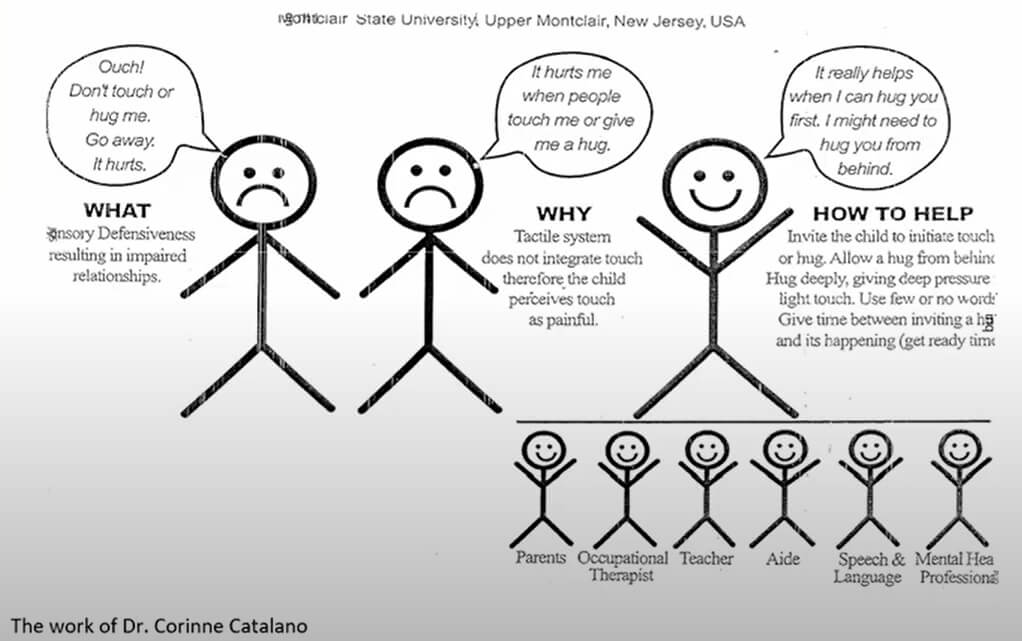

Colette says it’s so powerful when we understand our child’s cues and put meaning to them. She shared this diagram from Dr. Catalano’s work about how to make a document about your child. Colette suggests to also record:

- What happened right before the cue was sent?

- What was the cue sent by your child?

- What was the child’s reaction when you successfully read the cue?

- What might your child do if the cue is misread or missed?

- How can you repair the interaction or co-regulate if the cue was missed?

I suggested to Colette I could imagine a rolodex-type ‘document’ of cue cards with a hole punch in the top corner bound by a binder ring where school staff can add cues they notice at school for the benefit of the parent at home and vice versa. In other words, a dynamic, working ‘document’ that can have additions and edits as we go could be helpful.

Cues from verbal children and scripts

I also mentioned that many parents might believe that because their child is verbal, they can request what they want or need, but that is often not the case–and certainly not the case for all things, even if they have that capacity. Colette added that some verbal children may not yet be using language functionally, so while they might know what a banana is and be able to label it, they might not be able to request a banana if they want to eat one.

Colette also brought up children who script. A child who feels anxiety might script a line from a show they saw that was about feeling anxious and that is their cue to you that they are feeling the same. I gave the example that Jehan Shehata-Aboubakr gave us from our scripting podcast of the child who exclaimed, “It’s raining!” whenever anyone indicated danger because of an experience on a field trip where it started to rain and the teacher told everyone to get back on the bus by yelling, “It’s raining!” The more people who understand your child’s scripts and cues, the better understood they’ll feel. We listed a few more examples of scripts as cues for other meanings, including one from the Growth and Gaming podcast with Mike Fields.

Colette explained that these scripts help make meaning for our children when we read them as cues and apply them to new situations. When we go to sleep and I say to my son that we need to charge our batteries, he responds, “Like Stafford” from Thomas and Friends and that now has meaning for him, Colette says. If he then said we need to charge our batteries to someone else, they may or may not know that he is referring to needing to sleep, although that one is more obvious. Other scripts might be more subtle.

Co-regulating

Cue sending and reading is a large part of co-regulating with your child. Even if your child isn’t having a meltdown, if you miss their cue, they might just turn away and leave the interaction. Co-regulating can entice them to continue the engagement with you.

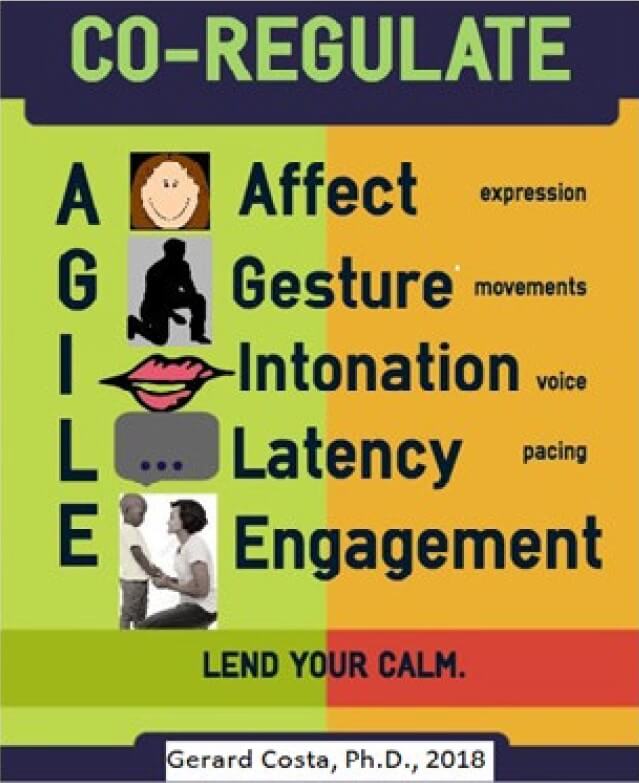

We want to have shared experiences, which happens when we read cues. Dr. Costa referred to the A.G.I.L.E. acronym to think about when you co-regulate as you can see in the diagram. Colette suggests these are important considerations.

I asked Colette to expand on latency which she explained is about pacing and how quick speech and movement can lose some our children. We need to slow down in order for them to be able to keep up.

Colette adds that this can be with movements in play, or even in giving directions. If we move too fast with a toy or a ball, our child might just see a blur and not be able to register it the way we do. And if we give three quick directions like, “Get your coat, your shoes, then go to the car” we might need to slow it down and stress each direction one at a time.

Thank you to Colette Ryan for this week’s podcast. I hope you enjoyed this topic and took some valuable insights from it. If so, please share this post on Facebook or Twitter and feel free to comment below with any relevant experiences, comments or questions. It would be great to hear some of your examples of cues your children send to you and how you came to recognize them.

Until next time, here’s to affecting autism through playful interactions!