Harnessing the Power of Narratives to Impact Development

This Week’s Topic

This week, we’re discussing personal narratives and harnessing their power to impact the Functional Emotional Developmental Capacities (FEDCs) including expanding emotional language, the concept of hindsight (e.g., should I have reacted that way), self-reflections, and more.

The topic of personal narratives is something Mahnaz has a great interest in and it spoke to me because I did my Master’s degree in Personality Psychology when the book by Dan McAdams came out called The Storie We Live By that talks about personal narratives, so to bring it into the realm of child development and DIR is exciting to me!

This Week's Guest

Developmental, Individual differences, Relationship-based (DIR) Model Expert and Training Leader, Mahnaz Maqbool, is a Speech-Language Pathologist in Pennsylvania, working with Mary Beth Crawford at Baby Steps Therapy, a DIR/Floortime clinic offering physical therapy, speech therapy and occupational therapy. She also teaches certificate courses for the International Council on Development and Learning (ICDL) and has taught courses and mentored internationally including in Pakistan and Bulgaria.

Mahnaz and I met at A Total Approach a number of years ago when she was my son’s Speech/Language Therapist at his Floortime intensive and we recently ran into each other at the DIR/Floortime conference in New York City.

What are Personal Narratives?

Mahnaz describes how an autobiographical narrative is the story that we share with others where we share our past experiences. She says that personal narratives fit so beautifully with the DIR Model. They come into play in social interaction, conversation, and for forming Relationships, which is the heart of DIR/Floortime. We share our experiences, emotions, information, and humour to make meaning of our experiences, Mahnaz says. Mahnaz was struck at the NYC conference by a simple phrase that DIR Expert Colette Ryan said: “And then I thought about it.” What it really means, Mahnaz explains, is that in retrospect, I reflected on the experience, and then shared it in personal narratives.

What are some of the foundational skills that we need to create these narratives?

Mahnaz explains that gaze stability, as discussed in this past podcast with Mary Beth Crawford, is necessary to develop affect cueing and emotional signalling which leads to understanding both our own intent and also the intent of the other. In addition, bilateral integration of both brain hemispheres leads to visualization, she continues. This is something that begins very early on as kids understand that mom is still there even though she went into the other room. It starts at this concrete level, but it becomes more abstract and complex, Mahnaz explains. We rely on these visualization skills to recreate our past experiences and then rely on our language skills to share these experiences with others, she says.

Occupational Therapists talk about being able to cross the midline with your arms, for example (i.e., left hand across body to the right side of your body), but in Physical Therapy, Mary Beth Crawford talked about the importance of gaze stability. I gave the example of the struggle my son has catching a ball and brought up what Occupational Therapist, Joann Fleckenstein, asked in our podcast about praxis: Can you predict that the ball might go to the right and move in that direction to catch it? Mahnaz says that your capacity for gaze stability will affect that.

In terms of challenges with visualization, I explained how my son understands how I’ll pick him up from school at the end of the day, but anything more abstract is challenging. He can visualize what he’s already seen, such as in a video game or cartoon, but is not able to imagine what he hasn’t seen. Mahnaz says that kids who have visualization challenges might be able to list off events they’ve done or places they’ve been to, but they struggle to recreate the emotion they were feeling at that time. That’s the important piece we want to recreate and help them understand how they felt about it, along with the language skills to be able to share that.

It really relies on not only visualization, but also on your short term memory skills, Mahnaz continues, that are needed to recreate events and the emotions–whether it’s talking about the scary house, or the nice teacher. We rely on our memory for facts of the experience, but we need the emotional piece for the social connection, she says. In school, we focus on the brain work of narratives in the story retell, but for the kids that we work with, Mahnaz adds, we need to focus on the personal narrative of what they experienced in time.

The sense of time comes in the 6th Functional Emotional Developmental Capacity (FEDC 6). Even though my son can understand that his friend’s birthday party will be next Sunday and school will start in a week, he still struggles with a sense of time. He might say to me that he wants to be picked up at 6:30, and I’ll correct him and say an earlier time, but he’ll protest and exclaim, “No! 7:30!” not really understanding that that is later in the day. This goes back to Dr. Stanley Greenspan’s Affect Diathesis Hypothesis, which my very first blog post on this website was about–how our children struggle connecting their emotion and intent with their motor plan and actions.

Focusing on Emotion

We have to start with very strong foundational capacities and strong affective communication because even when we share our narratives, we are thinking about the intent of the other person–how much to share, how much detail to give, et cetera. It’s at Capacity 5 where we’re thinking about emotional interoception kicking in where children have had a wide range of nuanced emotional experiences and make sense of it not only for themselves, but from another’s perspective. It’s about using this skill in the social world.

We have 2 different kinds of narratives. We have children who are able to add emotional themes to their narratives (episodic autobiographical memory where the emotions are strongly coded), beyond simply sharing a list of experiences (semantic autobiographical memory). Children diagnosed on the autism spectrum have greater challenges with episodic memory compared to semantic memory, e.g. personal narratives with reduced retrieval, specificity, elaboration, coherence, detail, emotional themes (Anger et al.,2019, Brown et al., 2012; Lind et al., 2014). This affects both past memories and projection into the future and can lead to challenges in the formation of a sense of identity and internal state language (e.g., emotional concepts, internal motivation).

This is why we spend so much time feeling the emotions in the fourth capacity and sitting in them so we can make sense of them. I shared how I started with my son by saying things like, “Wait a second. I don’t think he’s listening. I don’t think he’s interested. Maybe we should check in.” just to put it on his radar over time.

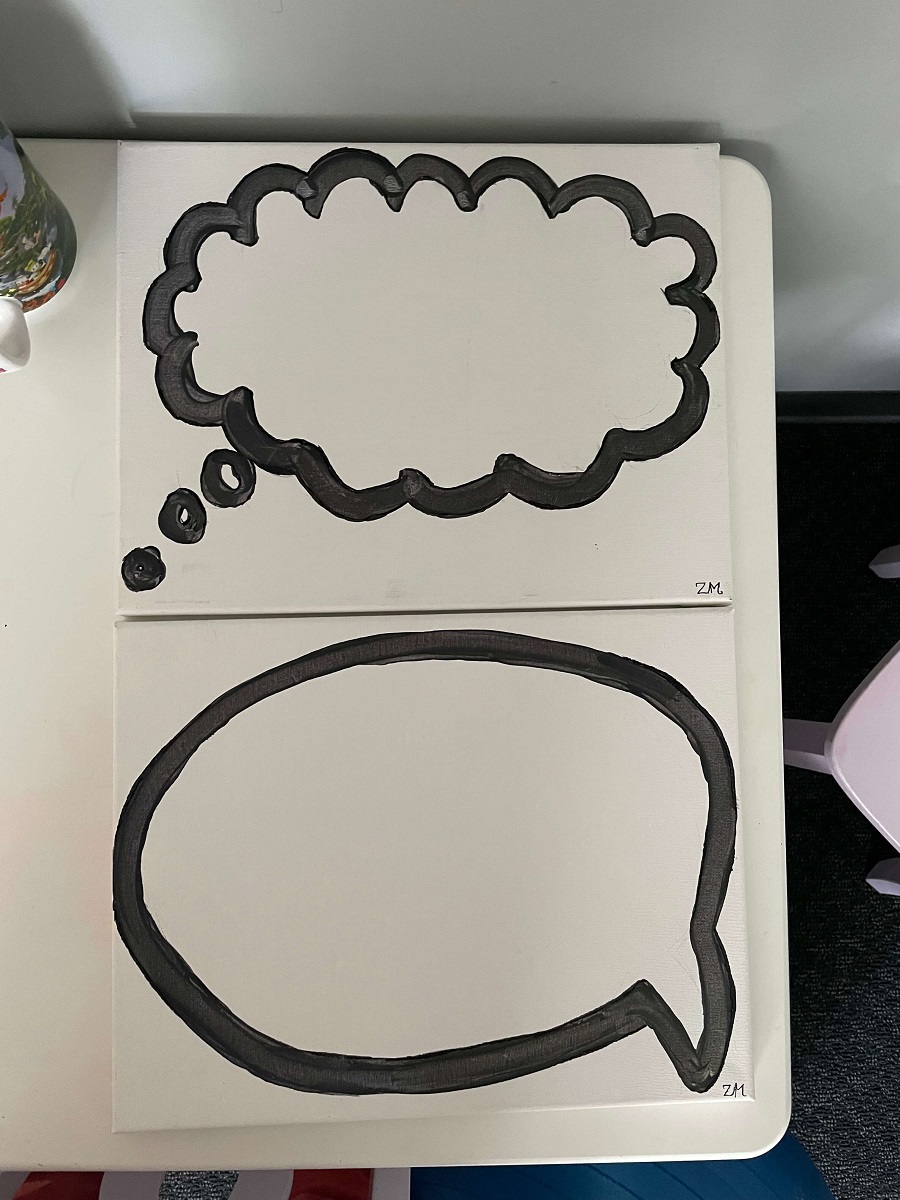

With me, I’ll say, “Wait a second! I don’t want to talk about that right now!” to get him to notice what’s going on in another person’s mind that’s different from in his own, as Dr. Gil Tippy stresses is what we do in Floortime. Mahnaz says it’s like picturing thought bubbles over someone’s head and wondering what is in their thought bubble. What are they thinking and how do we share that?

It’s usually nonverbal and affective communication that’s conveying that. How do I know if someone’s interested in what I’m saying? Did I lose them, and do I care if someone’s no longer interested? How do I shift? I love that idea of picturing thought bubbles. Mahnaz uses painted thought bubbles to make it a bit more concrete.

She says that on YouTube you can slow down a video to 0.75X speed and she sometimes feels like we need to hold time and slow it down to give our children time to process what’s going on and the emotion, and take a minute to feel and understand it. The reflection comes after that. What did you feel about it? What do you think about it?

The Language of Emotions

When we’re thinking about narratives, Mahnaz, a Speech and Language Therapist says, it’s very heavily language-based as well in terms of using tense and detailed vocabulary. Beyond that, though, she says, we want to focus on is ’emotional state’ language including internal emotions and internal motivations.

How did you think about something? How did the other person react? It has implications for social interaction, but in the academic world, let’s think about reading comprehension, she suggests.

Once we have the ability to visualize in reading, Mahnaz continues, you can take the arbitrary words on the page and create a very strong visual image that can be manipulated. This informs what the character thought and why they thought that, and you can then ponder what you would have done.

This work we do on foundational skills has strong implications for what we do in future academic work, Mahnaz continues. There are kids who are hyperlexic. They can read and answer all the concrete questions, but struggle with the higher-level abstract questions. This is where reading comprehension starts to fall apart. If we were to come back, we can then look at how they do with formulating their own personal narrative and how they listen to someone else’s narrative, she explains.

Many of our kids hate reading because they’re not feeling anything as they’re reading, so it’s just tedious. They gravitate to movies because the work is done. Graphic novels can be a good way to get children interested in reading, Mahnaz suggests, because you still have to use visualization to comprehend them.

Developing our Functional Emotional Developmental Capacities (FEDCs)

It made me think about my own capacity to visualize. I described to Mahnaz how I never had a problem with logic, analytics and math, but reading comprehension wasn’t my strong point–even though I did great at school. I laughed at how I’m annoying to watch a movie with because I sometimes don’t understand what’s happening in the movie and ask a lot of questions.

Of course, now that I am raising an autistic child, I feel this helps me relate with this experience as I work on my own visualization. I have noticed along my own journey that parents learn about their own Functional Emotional Developental Capacities (FEDCs) as we help our children go through theirs. We grow and learn together.

Mahnaz says that she, too, has learned so much about her own Individual differences in reflecting on her own capacities in her Floortime journey. If you see yourself over space and time, which is Capacity (FEDC) 6, you begin to develop a deeper sense of self and can go back in time and see that this is still me as a student, as a friend, as a baseball player, and then reflect on how you’ve changed, which gets into the higher capacities.

Neurodiversity and Personality Constructs

I shared that I raised the topic of neurodiversity in personality constructs with my former, now retired, graduate school advisor and he hadn’t heard the term. It’s an area for future research. I, myself, could never figure out why I didn’t seem to fit into some of the researched constructs. Mahnaz says we have a tendency to want to fit people into a box, but we are nuanced individuals. She prefers to describe personality through narratives over taking personality tests.

I also mentioned that I would love to get a self advocate’s perspective on this topic as well. The way autistics communicate is different. It’s not neurotypical. Maybe they notice intent in different ways. Many say they can feel it, but they don’t express it the same way neurotypicals do and they don’t have the same affective signalling that neurotypicals do. I look forward to looking into this perspective, and have some ideas, based on my own experiences.

Promoting Personal Narratives

When Mahnaz talked about the importance of language, I asked about non-speaking individuals, and she clarified that it’s about communication, including affective and gestural, etc. Being able to understand it within yourself, then being able to share it is how we make connections, she explains. We can promote this in our children by reflecting on experiences in more nuanced ways. When we ask kids, “What did you do in school today?” we might get responses like, “Nothing“. We need to know if our child can you visualize across space and time?

In addition, our children might wonder without saying, “Are you interested that my pencil broke or how my test went?” Maybe it’s that they don’t see the value in sharing this information with you right now. As adults, we can model our narratives by sharing our process of internal thoughts such as sharing our own thought bubbles. It doesn’t have to be a teachable moment, Mahnaz says, but a simple statement about being frustrated that you let your gas tank in your car go to empty, for example. “It’s making me feel agitated. I did this 2 weeks ago, too. I won’t do that next time.” When we think about narratives, it’s thinking about the past in order to plan for the future, she stresses.

Personal Narratives Promote Regulation

As parents, we have this tendency, Mahnaz says, to say what’s coming up. We talk about what we’ll do on Thursday evening or on the upcoming weekend, but do we ever reflect upon the past, she asks? “Remember swimming class from last week? You were a little nervous about that. What can we do for next week?” We reflect on the past to prepare for the future. It’s powerful to create that visual image in order to understand our own emotions for the future. It brings us a strong sense of regulation as we understand our process.

Personal Narratives Promote Agency

The other beauty about telling your own, Mahnaz adds, is that a story brings a sense of agency. I get to tell the story from my perspective. Often parents tell the story for their child. A general Floortime principle is that we want to promote that agency. We’re so used to running the show as parents. It’s really hard when you stop controlling and let your child initiate. This is one example of how to do that. Infuse it into our daily world, Mahnaz says. We engage with one another by telling our personal stories. Think about what we’re adding to these stories and what we’re thinking about, which helps our children.

Language Praxis

Language praxis is something we have to think about, too, Mahnaz shares. How we think about praxis is usually in the body, but if we were to overlay language there’s a lot involved, she says. There’s the ideation: what do I want to talk about? There’s the execution and sequencing: having the right words in the correct syntactic organization of the sentence, with the right timing, affect, and gestures. It’s complicated, Mahnaz explains. Is the person still interested in what I’m saying? Am I giving too much detail?

I shared how I am a details person and often get teased about making short stories way longer and more detailed than they need to be. It made me think about Damian Milton’s Double Empathy Problem where autistics communicate well with other autistics and neurotypicals with neurotypicals, but neurotypicals struggle with autistics and vice versa. Praxis is about planning what I’m going to say, but if something unexpected comes up, can I pivot and stay with the conversation?

Perspective Taking

When we’re forming narratives, we’re building self-regulation, sense of self, and also theory of mind, Mahnaz says. What is the other person thinking? This is what I think. I don’t agree with you, or I do agree with you. Last time, you said this. This time, you said this. It’s about being able to think about the other person’s thoughts, as well. Who’s telling the story? Who’s point is this? We want to hear about the details that are significant to our children and what they experienced, emotionally. We want to make sense of an experience. The light bulb moments come when we share our experiences with someone and reflect on them. We can always get stuck in loops of what the other person thought. We can never actually know.

Emotional Experiences and Interoception

We want to emphasize the emotional component and the emotional experience of narratives, Mahnaz emphasizes. I gave an example about how in Cognitive Behaviour Therapy you might reflect on an experience, how that other person reacted, and what you thought and felt about what happened. It’s a story you made up in your head and you plan on changing your story the next time it happens. That is a very cognitive exercise, whereas we want to focus on the emotional experience in the reflection.

Parents tend to want the uncomfortable emotions–typically called negative emotions–to disappear, but all emotions are important, Mahnaz explains. It’s important to sit in your emotions, feel them, understand them, and then reflect on them (i.e., “and then I thought about it“) with narratives, and then be able to share them with someone. You can then take a step back and see things more clearly. You can harness the power of storytelling for developing the sense of self, and more.

Self-Confidence

Creation of personal narratives and telling our story impact self confidence versus stories we tell ourselves in our head. You may have had a bad experience from getting bullied and you may beat yourself up inside if you blame yourself. That kind of story-telling is a bit different than the personal narratives that we’re talking about, Mahnaz explains. We want to foster in our children the idea that you can’t control what other people think of you or what they’ll say or do, but you need to have the agency to be comfortable enough with yourself to say you really feel and think.

Amy Pearson and Kieran Rose just published a book about autistic masking. Personal narratives come into that topic as well. The stories we tell ourselves are our internal monologues can be turned into personal narratives when we share them and get another’s perspective on what we said. It’s powerful to put it out there. They might offer a different perspective that contradicts the story we created about an experience, which can impact our self confidence, especially if it stops us from beating ourselves up about something we misunderstood.

Making Connections

DIR/Floortime is all about the ‘R’ and building connections and the power of sharing is very important. How we make connections is affected by how we expand our narrative capacities. It looks different from Capacity 5 to Capacity 9. Usually in the teen years we start to have the idea of a life story. Mahnaz gave the example of her teenage children remembering when they were in their old house, visualizing it, remembering how they felt at that time and bringing it into today. They defined how they’ve grown and changed, but only when they shared it and were remembering and adding depth to their stories.

People also remember things in different ways and associate things with places, smells, or music. To prompt different types of narratives, you can use the thought bubbles, but you can also talk about places. Do you remember how you felt when you were in Strasburg seeing the trains (or when you ate a certain meal, etc)? Try to get to the multisensory piece of the narrative.

Benefits of Focusing on Personal Narratives

Every discipline can harness the power of narratives whether you’re an OT, an SLP, a PT, a teacher, etc.

- Narratives are important for building a strong sense of self (McAdams, 2018).

- Narrative skills are highly predictive of social and academic success. Not being able to share personal experiences with others in an emotionally meaningful way may affect ability to establish relationships with others.

- Narratives help build self-regulation through being able to reflect on past experiences, and in episodic future thinking (Tulving,1985).

- Narratives help develop theory of mind/perspective taking.

- Narratives help with development of language skills (i.e., syntax, semantics, sequence, main idea, detail), which are reliant on strong praxis skills.

- Narratives foster reflecting on past experiences and being able to plan for the future, including making sense of experiences, e.g., how/why something made one feel a particular way.

- Narratives create connections with others through sharing experiences.

- Narratives foster a sense of belonging in the larger community.

- Narratives help with remembering a full emotional range of episodic memories versus just listing facts.

- Individuals with constrictions at Capacity 5+ are likely to have difficulty sharing personal experiences with others in a way that allows them to be part of a group, and can lead to mental health challenges (Cooper et al., 2017).

- Parents who model personal narratives have children who are more likely to engage in personal story-telling.

- Traditional therapists focus on story retell, including elements of story grammar, syntax, and semantics, but emphasis needs to be on personal narratives. Model narratives, ask open-ended questions, and connect with emotions.

Credit: Mahnaz Maqbool

References:

Anger M., Wantzen P., Le Vaillant J., Malvy J., Bon L., Gué-nolé F., Moussaoui E., Barthelemy C., Bonnet-Brilhault F., Eustache F., Baleyte J., Guillery-Girard B. (2019). Positive effect of visual cuing in episodic memory and episodic future thinking in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, Article 1513. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01513

Brown B. T., Morris G., Nida R. E., Baker-Ward L. (2012). Brief report: Making experience personal: internal states language in the memory narratives of children with and without Asperger’s disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42, 441–446.

Cooper, K., Smith, L. G.E., & Russell, A. (2017). Social identity, self-esteem, and mental health in autism. European Journal of Social Psychology, 47, 844-854. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2297

Lind S. E., Bowler D. M. (2010). Episodic memory and episodic future thinking in adults with autism. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 119, 896–905. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020631

Lind S. E., Williams D. M., Bowler D. M., Peel A. (2014). Episodic memory and episodic future thinking impairments in high-functioning autism spectrum disorder: An underlying difficulty with scene construction or self-projection? Neuropsychology, 28, 55–67. https://doi.org/10.1037/neu0000005

McAdams, D.P. (2013). The redemptive self: Stories Americans live by. Oxford University Press.

McAdams, D. (2018). Narrative identity: What is it? What does it do? How do you measure it? Imagination, Cognition and Personality: Consciousness in Theory, Research, and Clinical Practice, 37, 359-372

Siller, M., Swanson, M., R., Serlin, G., & Teachworth, A. G. (2014) Internal state language in the storybook narrative of children with and without autism spectrum disorder: Investigating relations to theory of mind abilities. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(5), 589-596.

Tulving, E. (1985). Memory and Consciousness. Canadian Psychology, 26, 1-12.

This week’s PRACTICE TIP:

This week let’s model reflecting on our emotional experiences for our children.

For example: Talk about something that you experienced in the past (whether recent or older) and reflect on how you felt in that moment, such as a time you went to a fun place with your child and you felt excited about being there.

Thank you to Mahnaz for taking the time to explore personal narratives and the Functional Emotional Developmental Capacities. I hope that you learned something valuable and will share it on Facebook or Twitter and feel free to share relevant experiences, questions, or comments in the Comments section below.

Until next time, here’s to choosing play and experiencing joy everyday!