FREE Insights this week!

FREE Key Takeaways this week as a New Year bonus! Enter your email above for access!

Happy New Year! To start off 2022, retired special educator, DIR Expert Training Leader with the International Council on Development and Learning (ICDL), and coach with ICDL’s DIR Home Program, Jackie Bartell, and Occupational Therapist Sanjay Kumar, who has worked in the company of Dr. Stanley Greenspan, currently works with an international school and does online Floortime consulting, join me to discuss the metaphor of a rubber band in supporting development, their presentation from ICDL’s 2021 DIRFloortime Conference. Sanjay came up with the idea when trying to explain Developmental, Individual differences, Relationship-based (DIR) Model concepts to parents.

The Rubber Band Metaphor in Floortime

We all want ‘instructions’

When talking to parents about bringing the learning alive in their children, and about the sensory organization, Sanjay would share how important it is to maintain arousal and attention. He found that parents tend to look for a ‘recipe’. They ask about a sensory diet and they ask how many times each day to do it. They want to make it regimented, he shares. However, it doesn’t work that way. The learning is about bringing a little bit of stress into our interactions, and it is a dynamic process. If there is more stress, energy depletes faster, the child becomes aroused and loses attention.

Sanjay demonstrated that if you simply hold a rubber band, you can’t get tension. It just dangles. The challenge for the parent is to keep tension in the band, which means providing just the right amount of appropriate stress, Sanjay explains. It’s about determining what kind of sensory input needs to be put in place so that the tension remains, and then you can bring it back to the learning perspective again, he says. The rubber band metaphor made it easier for parents to grasp this concept for him. He says we have to keep some stimulation going, in order to keep the arousal happening, so that attention can go on. This helps parents understand the dynamic system.

Finding that ‘Just Right’ Tension

When I facilitate ICDL’s online parent support drop in, I see how lost parents feel, especially early on, with how to interact with their child and promote those interactions. They’ll see their children playing on their own, seemingly in their own world. My son would walk across the room and throw toys, dump bins, and wander seemingly aimlessly. Parents start learning about the sensory profile and there’s so much to know because it’s so different than other approaches, and they really are looking for instructions.

It’s not to say that some instructions are a bad thing, I added. I gave the example of how Occupational Therapist, Maude Le Roux, has given the tip to provide a good, deep pressure massage to my son upon waking up and before bed and how this can do so much for many of our kids. Here, though, Sanjay is talking about learning throughout the day, whether in school, or at home, where applying the ‘just right‘ tension is so important to growth. Parents and professionals try to figure out how to help our children become a part of a shared world. Floortime tells us to join the child and follow their lead. We might start by joining our child in emptying the toy box with them, but if we don’t apply some tension, it won’t support growth.

As we move along the developmental ladder of the Functional Emotional Developmental Capacities, we have to support the sensory profile in order to get the arousal and modulation in the ‘just right‘ place so we can support our children. We want to give some tension and stretch the rubber band to promote development, but not add too much tension, Jackie explains. And we go with them, she adds. We find ourselves inside that rubber band with the child as we provide the opportunity to build the tension so the child can make that developmental progress. It’s not the child’s rubber band, or yours, it’s our rubber band, she adds.

Example

I gave an example of when my son, who is a sensory seeker with motor planning challenges who loved cause and effect and knocking things over, was in the sensory gym. My son loved to build towers with the big gym blocks but wasn’t really able to build it on his own at the time. His way of getting that done was to tell the person who was with him to do it. When we were working with Occupational Therapist Maude Le Roux’s clinic, Maude told us he can do it, but he doesn’t have the confidence. She said we needed to hold him in that space, which is tension. We can use affect and wonder what block will go next, slowing it down to support him. But if we challenge him too much, or provide too much tension, the rubber band will snap and he’ll just kick the blocks over, giving up, and maybe try to leave the room.

When the Learning Happens

Sanjay says that we want to hold engagement with the child through the relationship and affect in that space. While that is happening, the affect is being processed through the sensory information coming in to the child. Choosing the activity of the big blocks in the above example means that we are allowing large movement in the large space, Sanjay adds, which allows the child to apply the visual-spatial thinking of the large blocks in the larger space to assist with his motor planning with big movements. We are holding it up and providing an activity that is meaningful to him, and is developmentally appropriate as well.

There’s a sensory appeal, Sanjay continues. The larger movements are helping the larger sensory systems (i.e., touch, pressure, movement) to keep the arousal connected while the relationship is connected, helping him process the visual-spatial information by fitting the blocks together on a tower, which becomes a developmental pattern of learning the motor plan of how to make this tower. This is something that my son loves and wants to do, I emphasized, but it’s hard for him, so he gets discouraged and gives up. But we want him to know that he really can do this, and that we’re there to support him to do it (i.e., the relationship).

He would take a triangle block and put it up with the point on the bottom and it would fall over. Until he gets the practice with that, he won’t know that. It’s figuring out what works and what doesn’t. With motor planning challenges, this process doesn’t come naturally and when it’s too hard, he just wants to kick it over and give up. So when we hold him in that space, we are helping him do what he wants to do. You can see the joy and pride on his face that he is building the tower successfully. The more he does that, the more confidence he gets.

A Contrast to ‘Compliance’ Models

We have to keep in mind that we are working with the child, not forcing the compliance of teaching him how to build a tower because he must learn how to build a tower, to stick with the above example. Jackie suggests that when he put the triangle on the wrong way, I never said, “No!” I said that actually, I probably did in order to try to teach him the right way, especially early on, as demonstrated in the videos in the early episodes of the new Floortime series, ‘We chose play‘. But as I learned Floortime, Jackie said I might have said ‘no’ in an affectively engaged way.

I might have suggested, “What about this way?” to stay in the moment and try something new to demonstrate that you can manipulate the block to make it fit differently. Without being comfortable holding the tension in that rubber band, our inclination is to just say, “Do it like this.” It’s what many parents do when they teach and show their kids how to do things. As I got more Floortime coaching, I learned that you let the child experiment and hold that space, which is providing that foot on the gas and brake at the same time, as Dr. Gil Tippy described it. If you suggest a different way but your child doesn’t know what that means, you suggest an easier way until it’s just the right tension.

You are experiencing the learning with the child, Jackie adds, but you have to be comfortable with the tension that it promotes. It’s possible there will be a moment of frustration. Many parents aren’t comfortable with the tension and we don’t want to see the frustration in our child.

Frustration is ok if the rubber band doesn’t break.

Generalizing Learning

Sanjay adds that if he’s teaching the play, then it won’t be a satisfying experience to the child. It’s that satisfying experience that brings the internal growth for the child, he explains. If the child has internal growth, they feel satisfied and like they achieved something. They feel great. But if the child is just going through the compliance model and hitting it the same way, they’ll do it, Sanjay continues, but it doesn’t generalize. It will not have the generalization capacity, so it ends up being a generalization task. It becomes one task after another task after another task. It leads to a revolving door kind of practice where you keep teaching and after awhile you are tired. You feel like you keep teaching the same thing over and over, but that the child cannot apply it. It’s exhausting, Sanjay exclaims.

If I was teaching the play, then the play will never look like a satisfying experience for the child which brings the internal growth for the child.

When we are applying the DIR model and moving through the developmental capacities from regulation through engagement to circles of communication to social problem solving, and the tower is done, the child sees that that’s the way they wanted to have it. That’s great! Now the child feels they can do it and can crash it down and it will be more fun. It fits into the child’s sensory appeal, Sanjay says.

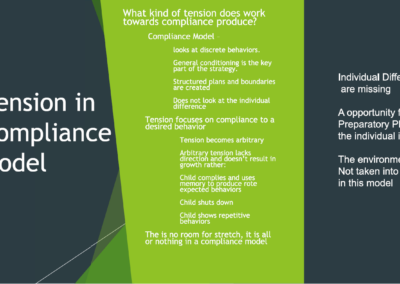

Compliance Doesn’t Support Growth

Our society wants children to be compliant, Jackie and Sanjay say. Perhaps this is not the best way to look at the growth process and the developmental process in schools and at home because it only looks at discrete behaviours without looking at the child in a more general sense. It doesn’t look at the individual differences each child brings. In the example of my son, if we don’t take into account his individual differences of having motor planning challenges, and only focus on building the structure with the big gym padded blocks, it is just about him being compliant to that experience. It’s not really about learning because it becomes structured and repetitive. There’s no joy for the child.

The tension that is put into the compliance-based model focuses on being compliant to a desired behaviour, not to generalizing the behaviour, Sanjay adds. I shared how that experience of my son building those block towers has progressed into his interest in wanting every Super Mario LEGO set where he uses an app to build these elaborate LEGO sets step-by-step. Dad helps him figure out how to rotate the pieces and put them together to build these characters that he loves. He’s progressed from this big gross motor space to this fine motor space of putting blocks together.

If he was just being taught to please the therapist, it doesn’t help him build the LEGO now because he’s sitting and waiting on how to comply and he doesn’t know how to build it. Jackie adds that there’s no opportunity for stretching and tension if he’s just being taught in the compliance model to do the steps in the sequence to build the LEGO. Learning the Floortime way will help him learn to put together the BBQ set when he’s older, Jackie offers. The compliance model does not support growth and generalization.

Memory Work versus Learning

Sanjay adds the important piece about how we play with memory work in a compliance model. After awhile in a compliance model, if you don’t use it, you lose it, he explains. There is no learning. Sanjay would see children who were doing the same things at age 12 as they were at age 6 when they were receiving a compliance model. The foundation wasn’t there. The memory method didn’t work at all. As they grew older, the whole sensory piece was so difficult to manage because the children grow so big. In the longitudinal perspective it doesn’t bring a real change, he reflects.

Body Awareness Learning

If you’re just being taught to be compliant around a discrete set of skills, Sanjay explains, children don’t learn how to manage their body because they’re not given an opportunity to explore the sensory world. In the large gym, my son was not only given the opportunity to understand how the blocks fit together, but he also had the opportunity to understand how his body fit in to those spaces. Without that, it can lead to adolescents picking up their caretakers and moving them to do what they want if they don’t understand the relationship of their body to another person’s body, if we don’t provide them with a safe space, inside that rubber band, so we can build a little tension to give the child those opportunities. These types of problems ensue later on with the compliance model, Sanjay continues.

Contrasting the Compliance Model with the DIR Model

In the Developmental, Individual differences, Relationship-based (DIR) Model, we look at the whole client from the inside out. We understand the sensory component of each child. We’re providing an opportunity to have that growth by providing the tension around those challenges while understanding who the child is first. We’re driven not by what we want them to learn, but by where they are developmentally. We provide tension to move up that developmental ladder. We also understand that the relationship we have is the modality that we have to support that tension and supports the opportunity for that stretch towards growth.

Evidence is showing that learning does not happen based on compliance. Learning happens through curiosity, connection, and co-regulation, which are cornerstones of a developmental model and a Floortime model.

When you learn how to ride a two-wheel bicycle for the first time without training wheels, you did it with someone you felt safe with, as Dr. Kathy Platzman said at the ICDL conference. Sanjay adds that if you just hold the elastic with one hand at the top without stretching it at the other end, then it’s just hanging loose. You have to add some tension to the elastic, or that stretch, into the child’s environment which can facilitate the growth and engagement to see the child’s developmental progress to their benefit, Sanjay asserts.

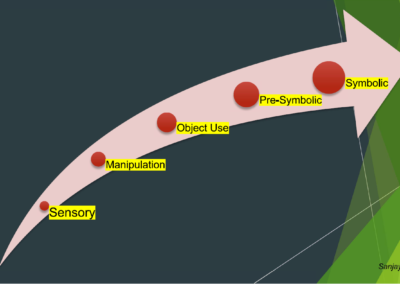

Moving Through the Developmental Capacities from a Sensory Perspective

When we start to engage with children, they want to have fun, Sanjay shares. Every child who comes to a sensory room wants to have fun because the physical sensory experience makes them feel great, he adds. But if it becomes stuck there, it becomes pathological, Sanjay explains. From their sensory experiences, they manipulate objects and learn how to do things with their body and objects, such as using a spoon and a fork, as one example. Now they know the body, they can control the body, their sensory systems are synchronized with the body, and so they can move. Now they have an idea that they can cut the apple or a piece of paper with scissors and make something out of it.

They learn single-step play with objects, Sanjay continues. As they grow older, they string these steps together and enter into the symbolic world. This is a developmental pattern that children move through. Sanjay referred to my example of how my son went from the big blocks and started to go into small LEGO blocks. Eventually he used objects into pre-symbolic, and now he’s into the symbolic. He wanted to do these activities from the sensory stage through to the symbolic stage, gradually, and developmentally, he explains.

I referred to the podcast with Occupational Therapist Keith Landherr called Co-Regulation is the Driver for Sensory Regulation. Like Sanjay said that the sensory experience on it’s own is not what we aim for, some parents think that they need to put up a sensory swing so their child can use the swing, but what we really want is to be a part of that swinging with the child, in an interaction while they’re swinging. If I had stood back and just watched my son throwing toys, he was just getting a lot of visual stimulation. Sanjay called that pathological because it wouldn’t be developing into something.

I showed examples in ‘We chose play‘ how I gave my son the experiences of throwing all different balls in different areas, in interactive games where it was more fun because he was doing it with me. Jackie says what’s important there is that I said, ‘we‘. I was throwing along with him, promoting circles of communication in a sensory space. And the key for Sanjay with the arrow slide, above, is that we want children to move towards symbolic thinking. So the challenge is how do we, as a therapist or professional (or parent), challenge the child so their sensory needs are met, and at the same time go to the symbolic level.

I added how important it is not to rush that. I give examples in ‘We chose play‘ where we played symbolically, and our son walked away because it was above where he was developmentally at that time. We are always headed there and have that in the back of our mind, and you might try a few things and realize that, “Oops,” the rubber band broke because it was too much. The child lets you know when it’s too much. They will protest in some way, or have a melt down.

Ruptures are Our Friend

When it’s ‘too much’ and the band breaks, Jackie says we get information about where the child is. It’s an opportunity for assessment. It tells us we have to have a little less tension. Children might be at the object stage of their play with symbolic toys and we respond with symbolic and they aren’t there yet. It made me think of siblings who are symbolic, so a caregiver might be playing symbolic with the siblings while the child we’re discussing might not be there yet, and that rubber band might break.

Jackie says that’s ok: you can get another rubber band that is smaller or bigger, and you start over again with co-regulation and connection using the relationship and affect. This is the opportunity to develop the emotional regulation, as well, Sanjay adds. It’s ok if it all falls apart because the child can realize they can calm down with that safe person and eventually get to the place where they can calm themselves down.

This week's PRACTICE TIP:

This week can we fulfill our child’s sensory needs while adding some tension to our rubber band?

For example: If your child is younger, this may be you playing innocent and not understanding their request. With affect, help them communicate with you just that little bit more about what they want. If your child is symbolic, you can not understand what they are explaining to you, wondering, “Hmm… I’m not sure what that means?” to stretch that band. It might be supporting them in opening a wrapper of something they want, like a toy or a protein bar. Instead of opening it for them, wonder together how to open it, like my example of wondering how to put the LEGO character pieces together.

Thank you to Jackie and Sanjay for bringing us this easy metaphor to help us grasp the complex concepts in Floortime. I hope that it made sense to you and helped you understand some things you didn’t quite get before. If you found it useful and helpful, please do share it on Facebook or Twitter and feel free to share relevant experiences, questions, or comments in the Comments section below. Stay tuned for the next podcast in two weeks on ‘cognitive load’ with Colette Ryan.

Until next week, here’s to choosing play and experiencing joy everyday!