Last week brought you some examples of process-oriented learning. This week, we continue with this topic. We heard Rae Leeper say that at the Rebecca School, this process looks different depending on the developmental capacity of the student. Julia Feltus from the Rebecca School provides some examples in this week’s podcast.

Facilitating process-oriented learning with developmental capacity in mind

The ‘D’, the ‘I’, the ‘R’, and Process over Product

Process-oriented learning is used to apply the Developmental, Individual differences, Relationship-based (DIR) model at the Rebecca School. Staff take into account where the students are developmentally, their personal and unique sensory processing profiles and other individual differences, and form safe, warm, and nurturing relationships so the students trust them.

Head teacher of the classroom, Julia Feltus, says that when she is designing curriculum, she is always thinking about the students’ developmental capacities: Are they regulated? Are they able to share attention? Are they able to sustain engagement? She’s also thinking about their interests and their passions (recall the affinities-based learning discussion last week).

She also has teaching assistants to help out when children need to be met where they are at if they are not ‘in it’ with the group. They might go and do an obstacle course in the hallway.

She will go with that because that’s how the students will be engaged for a longer period of time. For example, a student decided he wanted them to re-write the story and have the children eat the witch. So she went with it. This allows the students to release the higher capacity skills. It’s about the process not the product.

This also helps the students learn about the sense of time and work on rigidity. Sometimes there’s not enough time for a lesson. A student will say, “Hey it’s time for yoga now!” Julia will say, “But we’re working on something different now“. Life is not predictable. This is a natural way to work on changes when things don’t happen as you expect.

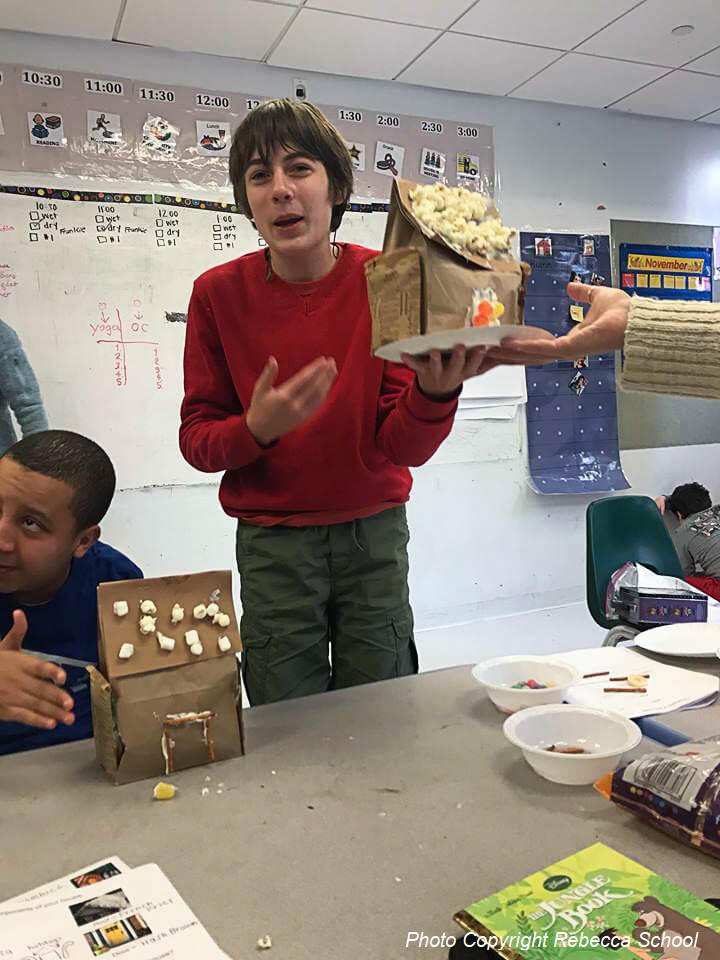

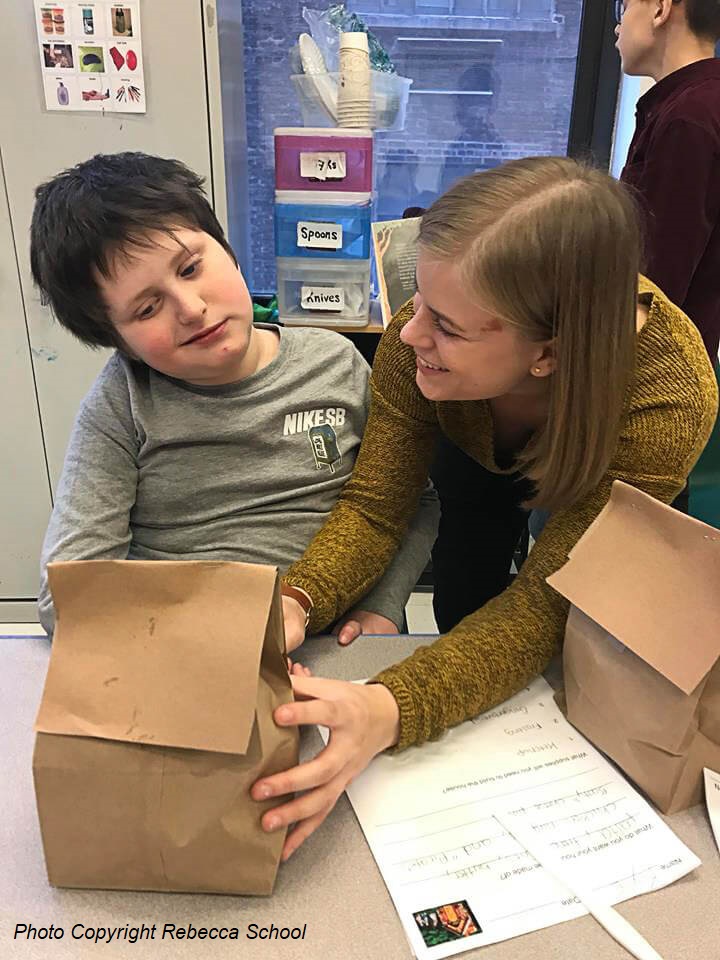

Teaching to different developmental capacities

Here both students get the just-right challenge because the helper student is widening capacity 4 to understand the other’s perspective, while the recipient student’s learning of how to figure out what to do when there are no forks is being scaffolded and supported by the helper student.

The hardest jump in development is from the third to the fourth capacity. A few of Julia’s students are at the cusp. The students who have the higher skills are filling in the holes at the bottom and the others are just getting there.

One student lost his blue cup. They only had a pink one. For over two weeks, he and Julia worked on what they would do. He wanted to colour it blue, but it washed off. Then they painted it, but the same thing happened.

Then the student noticed a peer who had a milk drink he really likes, so he took off the wrapping and laminated it and taped it around the pink cup so he’d have a cup like his friend’s milk drink. It wasn’t blue, but he liked it, and it was his idea. What was important to Julia was the 2-week process it took him to get there.

If something is easy all the time, we won’t know how to get through it when something is hard. The just-right challenge facilitates a necessary part of learning and growing.

When unpredictable things happen, there are students who drop down to the first capacity. The staff right away will change how they interact in the moment: they drop down to co-regulate until the child is ready. Julia gave us another example of a child who had an idea for a new Disney show with one of the teaching assistants as the star.

Co-regulating is about the “It’s going to be ok. We’re going to be ok. We’ll make it to the other end.” The staff scaffolds the students through the process so they don’t give up. Next, the staff reassures the student once he finally ‘gets it’, and later reflects with the student that “You did it!“

The students in these examples are able to get through their distress because of their Relationship with the staff member. Julia says that the students need to be able to trust you and feel comfortable because we’re asking them to be really vulnerable. She says that the Relationship is the most regulating thing for them–moreso than sensory regulation.

The ‘R’, or Relationship in the DIR model is empathic staff constantly attuning to the students. They are always co-regulating and practicing frustration tolerance and problem-solving in a loving and respectful way.

Dr. Gil Tippy, the clinical director at Julia’s school has pointed out to us before the importance of moving from the concrete to the abstract world where you realize that if you are really thirsty and want some water, it doesn’t matter if your cup is blue or pink because it’s the same water inside. Julia says that with a good Relationship, you can see where the students are on their road to abstraction.

If you found this post and podcast informative and/or helpful, please consider sharing it on Facebook or Twitter. Also, if you have any comments or examples of using process-oriented learning yourself, please consider commenting below in the Comments section.

Until next week… here’s to affecting autism through playful interactions!

This is such a helpful blog providing specific examples of applying the DIR model to group learning and social-emotional as well cognitive development . Thank you for reminding us of how Greenspan and Wieder’s beautiful framework can helpfully structure our thinking about what to do or say with students at various developmental levels to help them reach the next milestone !!!!

Thank you, Dr. Davis! It was a thrill to finally bring this to the readers of this blog as I, myself, have also wanted to know how it’s done! A wonderful model & framework, indeed…

Wow, that is a pretty insightful article. Thanks for sharing your views on the DIR model of learning for special needs kids. This topic was also brought up in a discussion at my daughter’s school, Rebecca.

Thank you, James. I agree. Julia is a great asset to the school!