Floortime Coaching for Different Parenting Styles

This Week’s Guest

This week I welcome Gabriela Michaca who is a licensed school neuropsychologist and also just received her Masters in Occupational Therapy. Developmental, Individual differences, Relationship-based (DIR) Model Expert and Training Leader in Los Cabos, Mexico. She recently presented at the International DIR/Floortime Conference in New York City about parenting styles and how to apply Floortime coaching with each style. As a parent advocate and with so many listeners of this podcast coaching parents when they do Floortime with their clients, I thought, what a great topic!

A Parent’s Developmental Capacities Affect Their Parenting Style

Parenting styles have effects on the relationship between parents and children and qualify their interactions during play and other family activities of daily life, Gabriela starts out. Depending how much energy you have and on your own emotional development, you will tend to have a particular parenting style, she says. She aims to figure out which one makes you feel more secure. When you’re stressed you can become more permissive, or go the other way and become more rigid, aggressive, or behaviourally-driven, she continues, which puts a lot of stress on both parent and children.

That is, depending on our own regulation as parents, our parenting style can change, Gabriela says. So not only are we are impacted by our Functional Emotional Developmental Capacities (FEDCs), but we are also impacted by the FEDCs of our children as well. It’s a dynamic system. You cannot look at the child in isolation nor the parent in isolation, Gabriela asserts. Parents also like different types of play. Some parents find sensory motor play dysregulating, Gabriela continues, while others find being seated and doing pretend play dysregulating. That’s why it’s important to set the type of play to both the child and parents’ FEDCs.

Parenting Style: Authoritarian

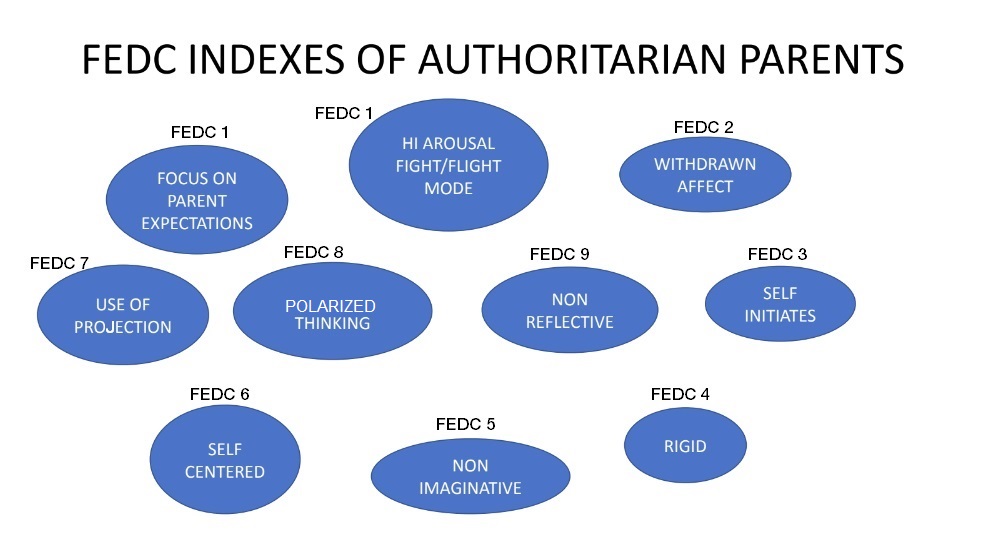

Baumrind (1971) described authoritarian parents as controlling and desiring behaviour according to the parent’s beliefs, having absolute expectations and having theological motivation. They value obedience. They favour punishment. The child’s actions are judged and the parent likes to feel respected by the child. Authoritarian parents don’t encourage dialogue and feel the child should accept their words as correct. They are prescriptive and give few alternatives. They use their power and firmness and give few explanations. They are rigid. They will withdraw love with discipline, Gabriela explains. She’s interested in knowing what brings this type of parent into dysregulation.

- FEDC 1: The parents focus on their expectations and don’t take into account the child’s perspective.

- FEDC 2: This parent is always trying to show you how much they know. They are inconsistent in withdrawing affection to obtain obedience. They either have an aggressive or a poker face affect.

- FEDC 3: They are very verbal and initiate most of the interactions and pay little attention to the non verbal cues of the child and this makes for them being obstructive during play.

- FEDC 4: If the child doesn’t do what the parent says, the parent becomes very frustrated. They become very verbal and rigid and try to solve the problem. They don’t give time to the child to solve a problem. If they don’t like the play, they end the play.

- FEDC 5: If the parent has an idea in mind, such as stacking coins, they won’t allow the child to play the game a different way. They don’t recognize their own emotions so they project them on the child in the play. They talk about the consequences of not following the rules. They won’t allow the child to share their own experience.

- FEDC 6: As we know, children need a lot of narrative to understand what they’re doing. These parents, though, become very frustrated and become polarized in their judgments. They make a lot of judgments. They struggle to understand the child’s behaviour or intentions and they tend to lecture the children.

- FEDC 7: The parent will project their emotions into the play.

- FEDC 8: The parent tends to be a black-and-white thinker with polarized views.

- FEDC 9: The parent is not able to self-reflect.

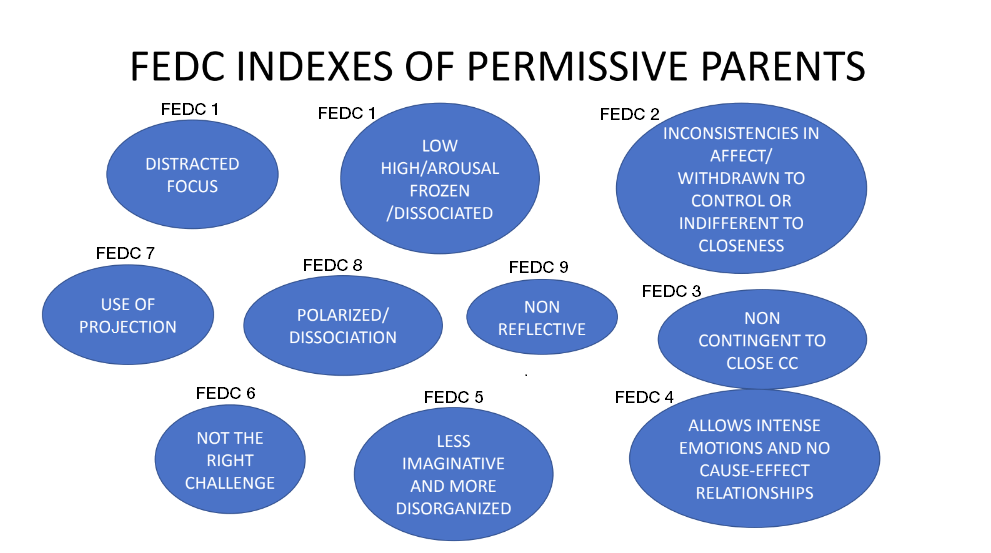

Parenting Style: Permissive

The permissive parenting style is not punishing, affirmative to the child’s impulses, and accepts the child’s wishes and actions. They give a lot of explanations. They avoid exercising control. They don’t motivate the child to obey and don’t define standards of conduct. They give a lot of opportunities for dialogue and are lax in rules. They are variable in their affect. The child doesn’t know what to expect because of their inconsistency. The parent projects their own experiences on the child and doesn’t provide questions to understand the different perspective of the child. They can interrupt the play because it goes against the natural consequences of intense emotions.

- FEDC 1: They tolerate the child’s regulation difficulties without containment. They are not able to co-regulate. They may lack energy and be distracted.

- FEDC 2: The parent is consistent in withdrawing affection, gives more autonomy, and has an indifferent affection towards the child’s needs of closeness. They might not be aware of what’s going on around them and their arousal might be frozen or dissociated. They are in a stressed state.

- FEDC 3: They are not contingent on the answers in the play and/or their answers are not logical. They receive the non verbal cues but don’t know what to do with them.

- FEDC 4: They allow intense emotions from their child. They don’t challenge the child or motivate them to solve problems together.

- FEDC 5: They do not bring new ideas to the game nor expand on what the child brings to the play.

- FEDC 6: They are unable to use the just-right challenge for the child.

- FEDC 7: The parent will project their emotions into the play.

- FEDC 8: The parent will dissociate and tend towards polarized thinking.

- FEDC 9: The parent is not able to self-reflect.

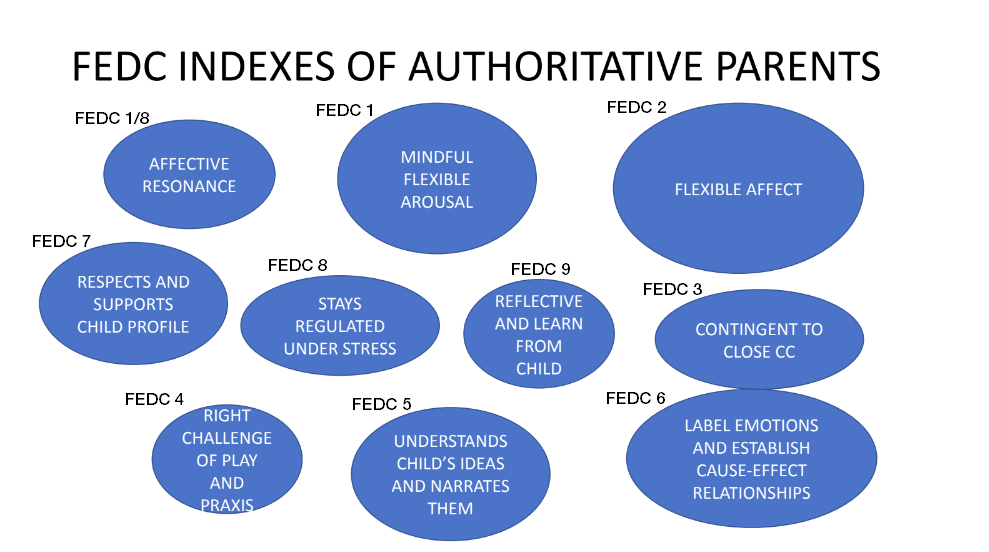

Parenting Style: Authoritative

An authoritative parent respects the child’s lead and supports the child’s activities. Their level of arousal is more flexible. It’s a more co-regulated parenting style. They value expression, autonomy, self-determination, and discipline. They are not punitive with the child. They are more mindful. Sometimes if they are tired, stressed, or have a lot going on, they can’t be, though, Gabriela explains. This style of parents is easier for practitioners, because there is less to coach.

- FEDC 1: Parent is able to provide predictability and is aware of how they modulate their regulation including their breathing so they are more present and are able to wait and follow the child’s lead.

- FEDC 2: They show closeness, empathy and affective resonance so they are more flexible. They know when to increase or decrease the affect and when to use anticipation.

- FEDC 3: They create pauses and allow for the child to respond and pay attention to the child’s verbal and non verbal cues and are more contingent to the child’s interactions. They can use obstructive play in a timely manner. There are less barriers to communication.

- FEDC 4: The parent usually generates an environment of trust and will stay solving the problem with the child, including scaffolding their activities. They allow time for turn taking.

- FEDC 5: They understand the child’s idea, or if they don’t, they can wait and wonder about the child’s intentions. They use language appropriately to build on different ideas in the child’s play. They are empathetic and flexible to simulate ideas and emotions in the play. They won’t get mad if the child’s play becomes more aggressive.

- FEDC 6: They’ll allow aggression in play, but in a constructive way by understanding cause-and-effect relationships and understand the child’s perspective, understanding that play is fantasy where we are allowed to make mistakes. Everything is allowed in play because we know we are just playing.

- FEDC 7: Not only can they tolerate intense emotions, but they can mimic them, and support natural consequences in the play. They stay in the play and respect the individual differences of the child.

- FEDC 8: They are able to stay regulated under stress.

- FEDC 9: They are more able to reflect and their communication is more assertive. They can learn from their child.

Coaching Different Parenting Styles

We need to be sensory- and trauma-informed when we coach parents so we can stop being judgmental and help them to understand themselves. We want to promote something different in them, but have them be mindful about who they are and why they are that way. It’s how we address and sustain them and how we can relate differently with them so they feel safe and secure with us as coaches.

Parenting Styles in a Floortime Framework

Gabriela says that these parenting style concepts come from more of a behavioural point of view. By reframing them through the Functional Emotional Developmental Capacities (FEDCs) and the Individual differences of the DIR Model, we can start to understand what’s happening under the surface. When coaching parents, they may not be in a space for self-reflection, she continues. You have to meet the parents where they are developmentally, as you do with the children, but in a different way. Bringing it into the Floortime framework allows us to understand how to coach the parents.

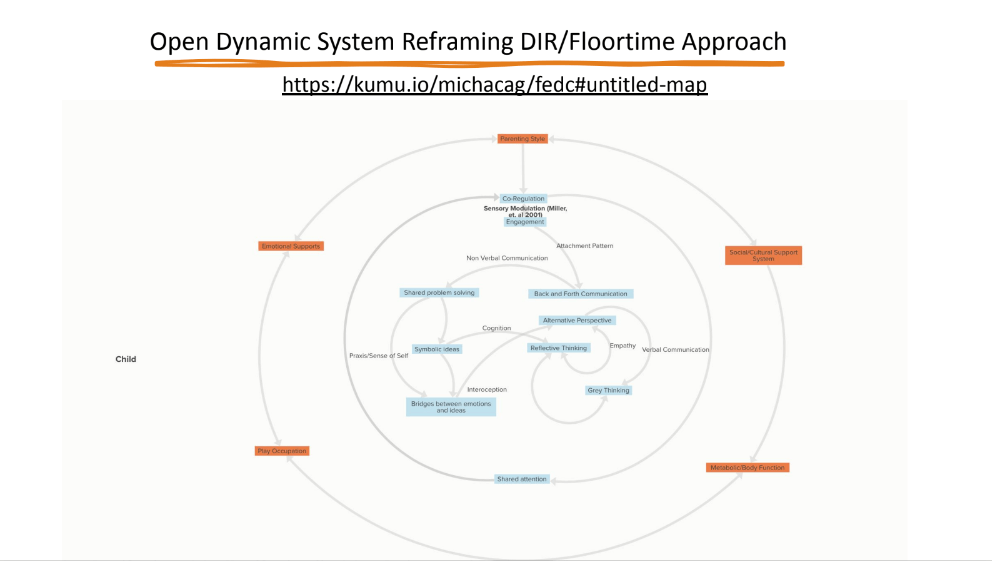

An Open Dynamic System

The process is not a developmental ladder, but a system. This is based on Dr. Stuart Shanker’s self-regulation paradigm. The parenting style is just an occupation and it depends on how much emotional and cultural support parents have, and on how much energy they have. If they have hidden stressors such as not sleeping or eating well, they won’t have energy to play or meet the child’s need for play. We might be asking too much from the parents, in this case.

When we think about co-regulation, we wonder if the parent is able to ask for support. Sometimes we have to ask them how they were raised so we can understand their core values and their own attachment styles. This is how they learned to be parents and we have to respect that. We can then see if the parent has problems with non verbal communication. How aware are they of how they express their emotions? It will affect back-and-forth communication and shared problem solving. If we understand their individual differences, it will help us plan how to coach them. Being self-reflective requires that they have this awareness, Gabriela continues.

Click on the above image to open it larger in a new window

If we see a more rigid style, such as an authoritarian parenting, we won’t see emotions. The permissive type will be overwhelmed. If we help them understand how their individual differences work, they will feel felt by us and start to understand what is happening with their child. All of the orange variables in the diagram impact everything blue in the middle of the diagram. This frame of reference has a lot of theory from Dan Siegel’s work of interpersonal neurobiology, Gabriela says. A lack of integration will affect how you will remember things, your emotion, and your sense of self, she continues, and how you use projection in playing with your child.

Seeing Another Perspective

Gabriela says that she would always respect the parent’s ideas, but she’ll also ask them to show her an apple. She’ll say tell me about an apple and a parent might reply that it’s green and round. Gabriela points out that that concept is only in your head. That’s an idea and ideas are always truth. That’s when the parent starts reflecting. “Ahhhh!” She will ask them how much they will live on their ideas? Then they realize that ideas are just a way to understand reality. That it’s your own interpretation of reality. Another reality might be that my apple is yellow.

Also, we have different interpretations of language. If I say you are ugly, can you tell me where the ugliness is? Gabriela says that she can say that I have on a black jacket and a blue shirt, but she hasn’t touched it nor seen it, so doesn’t know if it’s comfortable. She doesn’t know how I experience wearing them. We often assume things, she explains. It’s why we start wondering as practitioners and as parents, she says. It’s about wondering about the experience in other people’s minds.

This leads us to the Double Empathy Problem, Gabriela continues. The way that one person processes information might be different than how you do. What one person puts relevance on might be different than what you do. Who is not understanding whom? The therapist, the parent, or the child? We are an open system, she says.

A Non-Prescriptive Approach

There is no one prescription in DIR/Floortime, Gabriela states. Parents look for the answer to ‘fix things’, but as you learn more about Floortime, you see that it’s a larger dynamic with so many variables that all have moving parts. It is a complex system. We can simply add guidelines and put a framework around it about how to support parents and how they can support their children, including reflection to help ourselves as well. It’s very complex to understand, Gabriela says.

When we start Floortime, we need to be rigid around the Functional Emotional Developmental Capacities (FEDCs) because we need to understand the model. But once you learn more, you learn more concepts that you need to integrate in order to figure out what the family needs in that moment. It’s not a prescribed intervention, she asserts.

Dr. Neufeld said that a developmental approach is an insight approach, not a strategy-based approach. It’s about making people start to understand who they are, Gabriela suggests. We hold their hands and help them find their way, she says. It’s not my way; it’s their way, Gabriela says. We are trying to meet neurodivergent development, which is expressed differently and looks different than neurotypical development, she explains.

Tips for Parents

For parents who don’t have access to a coach and want to reflect on how they’re feeling when they play with their child, Gabriela suggests being mindful to yourself. Look at yourself with softer eyes, she says. We don’t have the perfect parenting style. This moves through time. If you need to eat, sleep, or exercise, take care of yourself otherwise you won’t face the stress you have in your daily life appropriately. Be kind with yourself, she says.

Also, be flexible. This is a learning process, Gabriela assures us. We’ll make a lot of mistakes before we find something that ‘works’. We look for our stressors. Also, be aware of the language that we use. Be careful of what you think, say, and feel, because sometimes the use of a lot of judgments will have a big impact on your emotions and thoughts, she says. Guilt is not useful, either. Give yourself time to learn, she encourages us. It’s not an easy approach. Enjoy the process. Be patient with yourself and with your child.

This week’s PRACTICE TIP:

This week let’s reflect on our own parenting styles when interacting with our children.

For example: Do you notice you change parenting styles when under stress? Be mindful of when you need to take a break to regain energy and what support you require to apply more of an authoritative style.

Thank you to Gabriela Michaca for helping us understand how to meet parents where they are at by respecting their individual parenting styles. I hope that you learned something valuable and will share it on Facebook or Twitter and feel free to share relevant experiences, questions, or comments in the Comments section below.

Until next time, here’s to choosing play and experiencing joy everyday!

Thank you so much to have the styles of parenting broken down and corresponding to the FEDC levels. I am learning to be a better “coach “. I am going to use the questions listed in the practical tips box next week.