This week we have a new guest. Developmental Psychologist and clinical Social Worker Dr. Cindy Puccio an ICDL Clinical Consultant and a longtime DIR practitioner and Expert Training Leader. She received her PhD from Fielding Graduate School’s Infant and Child Development Program and is a faculty member of the Sarah Lawrence College Graduate Program in Child Development. Our topic this week is humor development in autism and specifically the ways in which humor emerges, motivates, and expands our interactions with young children.

Humour Development in Autism

Research on Humour and Autism

I asked what sparked the interest in humour for her PhD dissertation and Cindy said that she had been watching it emerge for years, wondering how it would transpire. When she delve into it she was surprised at how difficult it is to define humour. For her it’s anything that elicited mirth or laughter in another but she saw what a complex topic it is. She was interested in how she was using it in a clinical way, and specifically in the Developmental, Individual differences, Relationship-based (DIR) Model. She quickly also discovered that there’s very little research on humour and autism.

What did exist in the literature was disappointing, Dr. Puccio says. It typically involved autistic children responding to a visual stimuli such as a cartoon or a funny movie, but what was completely factored out of the equation was another person, she explains. So humour transpiring in the context of a shared interaction didn’t exist in the literature, with the exception of a few studies. She understood why: it’s difficult to do when you have to take into account all of the variables. When you put humour in the context of a shared interaction it gets complex, but the complexity is really the point, she states.

That’s really unfair, she thought. How can people make comments about humour in autistic individuals when they’re measuring it this way. How can you fairly measure humour comprehension, production and appreciation without incorporating that shared, personal interaction component of it? It bothered her because in DIR/Floortime we think about playfulness, engagement, enjoyment, and motivation. Humour is a very important component of playfulness, but it’s often the driver. She really loves that humour is not pathologizing. Everybody has a sense of humour. It’s an individual difference.

When you open up a conversation about humour instead of deficits or challenges that others so frequently discuss, you talk about personality development and that is fascinating to Dr. Puccio. You can talk about humour as an individual difference as a response to a cartoon or a movie or as a construct that is co-constructed in a relationship, she says. When you look at it as part of a shared interaction, which is also called Interpersonal Humour, then you have so many more confounding variables, but they are all important.

Research Design

For her PhD dissertation, Cindy used a multiple case study for her research design since she wanted it to be clean, easy and doable. She looked at humour as it emerged in the context of a shared interaction. She looked at three cases of boys aged 3 to 5 who had an autism diagnosis and they were purposefully selected because she knew they had demonstrated a capacity for humour. She didn’t know what would emerge, but she knew what she was looking at.

She video taped eight Floortime sessions whom she had never met before in their home, where she felt humour could flourish since it was a safe, comfortable place. She was a DIR participant observer. Due to the subjectivity she did not analyze her own data. She transcribed each video tape and coded any interaction that elicited a laugh response from the child. It had to be audible laughter, not just a smile. A smile could have been more about enjoyment, so she wanted to eliminate doubt. When we think about humour, we pair it with laughter.

She looked at humour as it developed over the course of four months. She looked at humour embedded in the context of the relationship with her, and recorded the session. Often it did emerge because she laughed first. She looked at what surrounded the humour experience. Did this motivate the child to engage more or for longer periods of time. Her research questions included:

-

- What types of humour emerged in playful interactions?

- What is the response to humour when it emerges in a therapeutic context?

There was also a pre- and post-interview with the parent that asked about their child and humour to gather the parent’s perceptions about their child’s appreciation, comprehension, or production of humour. She found that the parents reported they had never thought about it and that it was fun to think about.

Themes of Humour that Emerged

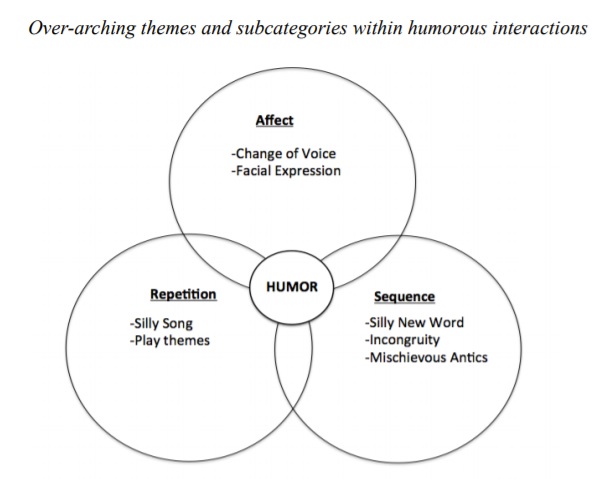

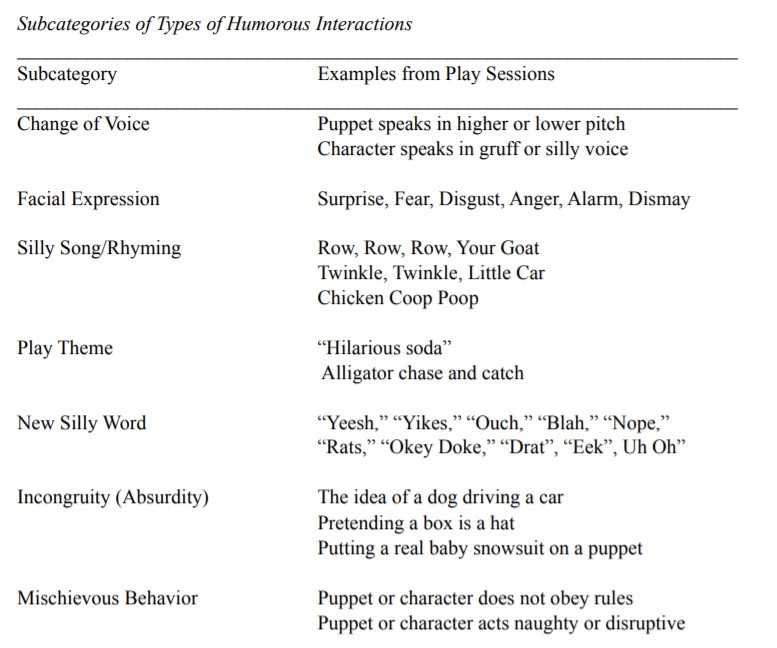

Three main themes of humour emerged from the study, as shown in the image below: Affect, Repetition, and Sequence. Dr. Puccio referred to Affect as play signals and found that negative affects were typically funnier including disgust, dismay, anger, fear, and shock (e.g., “Yuck!“). This did not surprise her considering the content of children’s television programs. She also added that some conflict is an ingredient in a lot of humour. The sub-categories of this theme of humour were Change of voice and Facial expression.

For the second theme of Repetition, Dr. Puccio points out that we often speak about repetition in autism in a derogatory way, but it serves a very important part in (everyone’s) development. Sesame Street uses repetition to their success, for instance. Cindy says that it can enhance trust through mutual enjoyment.

The sub-categories for Repetition were Silly Songs, which included changing the words of known songs, and Play themes which included a play schema created together that became funny to a child. The third theme was Sequence. Also Cindy states that all of the themes and subtypes overlapped and are interconnected.

Click on the above image to enlarge it.

The first sub-category for Sequence was New silly words, are referred to as ideophones in language development, Dr. Puccio explains. I shared that my son has always loved silly words and would laugh any time he heard them, then repeat them for months on end. The second was Incongruity (Absurdity) and the third was Mischievous antics. I gave examples of these antics that my son has enjoyed on cartoons.

Humour Promotes Development

When she looked at what preceded and followed the occurrences of this sub-type, Cindy found it so interesting that it puts children in a problem-solving situation. Someone didn’t do something the ‘right’ way. “What am I going to do about it?” It can even lead to imitating and initiating, she says. I said that that’s exactly what we do in Floortime, as well, when we get our children dressed and try to put the socks on their hands instead of their feet, for instance, to be silly.

Cindy also says that it also puts the child in the role of authority. Teaser: Next week’s podcast is about putting the child in the lead and the child as the director in Floortime with Dr. Amanda Kriegel and Mike Fields! These are all examples of how shared joy in Floortime helps drive development. Dr. Puccio says she loves the intersection of humour, playfulness, creativity and imagination. But the thing that pulls humour apart from the group, she continues, is that you can shift the feeling of the room with humour. We all feel better and more relaxed when we laugh. It brings out our genuine affect.

She continues that children can also appreciate humour even when they don’t understand it. Sometimes children will say something funny but not realize it’s funny, and we laugh. Then there’s also when they intend to say something funny and see the effect it has when others laugh. This is empowering and can also shift the energy in the room. It can boost their self-esteem. We can also give children affective cues to let them know that something funny is about to happen. This cannot happen with a photo of something funny.

Letting our Children Play

Dr. Puccio points out that in play we feel compelled to problem-solve for our children, but we should try to stop ourselves from doing that. Play is filled with conflict and aggression as children work through emotions. Parents tend to try to influence children in play by saying things like, “We don’t hit” or even playfully trying to put out a fire by saying, “Let’s get the fire extinguisher!” but Cindy says we don’t need to do that.

But what about when it’s not the time or place for humour, I asked? Dr. Puccio says that certainly there’s a time and place but making more time for unstructured play can always provide children with the time and space they need. Anytime we can make time to laugh together is ideal. Also, the inappropriate humour can sometimes mask another more important emotion. They might be uncomfortable or scared, anxious or restless. They might not want to stay at Grandma’s house so they are silly even though they’re not thinking it’s funny, but just want to leave.

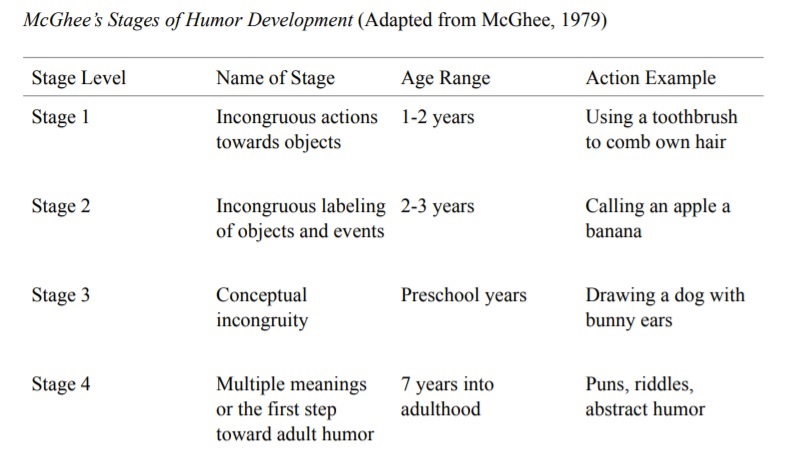

Stages of Humour

Dr. Puccio referenced the stages of humour that appear below and it made me think of examples of how my son has appreciated humour, shared in humour with me, and initiated humour with me. She said that the ‘private joke’ between two people is a very rewarding shared experience that we all love as we recreate a shared memory that was humourous. She also points out that humour can also be an important individual difference that can also just be a part of personality. It doesn’t mean that you have a disorder because your sense of humour is different.

Can we Facilitate Humour Development?

Dr. Puccio suggests using the sub-types of humour and examples as a starting point if you’re thinking about working on humour with your children. If you haven’t observed humour, you may not have observed humour production, but there are so many other layers of humour. You might feel more comfortable trying out some sub-types over others. Appreciate your child’s personality and what they may or may not find funny. It’s also possible to just be a more serious person, in general, and we all have different senses of humour. Your child may find different things funny than you do, and that’s ok.

Humour is an individual difference.

A huge thank you to Dr. Cindy Puccio for sharing her research on humour development in autism with us this week. If you enjoyed this podcast or blog post, please share it on Facebook or Twitter and feel free to share any relevant comments, experiences, or questions in the Comments section below.

Until next week, here’s to affecting autism through playful interactions!